It arose from begrudgement. The presumption is that Jake Fisher (77 kg, Curby 3-Style) wanted to talk. Though he is on the record below, the opposite was true.

Not that Fisher wishes to avoid sharing his story. That is another 180 of the facts. It’s more about the commitment, from both of you. He needs to be sure. The way Fisher sees it, if you are keen to learn his deal, to try and understand the wheels which spin inside of his head and the magnetocardiography reading from the heart that drives his passion, then you better come prepared. To him, the whole thing is an investment. A conversation is an investment. Especially when there are times the discussion feels akin to an exhumation. And the only reason why certain issues aren’t truly dead to Fisher is because he hasn’t yet had the chance to kill them again.

Part of Fisher’s frustration is, inevitably, intertwined with love. Otherwise, he wouldn’t care so much. Wrestling, specifically Greco, means something more to him, something different. This is why you, as an outsider, have to pass muster just in order to break bread. He doesn’t require you to love the sport in the same exact way; he positively does require you to fully acknowledge the honor he believes it deserves. If you’re not entering the fold with that kind of energy, how can you even begin the dynamic? Fisher doesn’t have a lot of time on his hands. The thought of wasting it bothers him more than actually wasting it.

When Fisher opens up regarding his perspectives on the US National program, and a mere sampling of the snags he witnessed or endured, he does not do so triumphantly. He is not celebrating an opportunity to bash those involved, past or present. Rather, to him, turning over the stones is almost a responsibility.

A bright, shining talent from Missouri who flourished under Ivan Ivanov during the old USOEC (United States Olympic Education Center) days at Northern Michigan, Fisher is convinced of American Greco’s relative salvation. But in his view, the only way that happens is through a similar loving devotion to excellence upon which he was reared. If this were not the case, if Fisher’s desire is to watch Greco burn itself to the ground, he would likely find little difficulty verbalizing such. To be sure, there are times when it appears that he is one sentence away from advocating for preservation through destruction — the act of destroying something you love before a corruptive influence renders it unrecognizable, useless, or both. Alas, that isn’t his endgame.

His words, as well as his recent body of work, are proof.

As a student of the sport equally equipped with a refined technical edge and a ferocious competitive disposition, Fisher was consistently deemed one of the country’s best athletes throughout the meat of his career. 2010 ushered in his first Senior National crown along with a spot on that year’s US World Team. He had delivered. Those in-tune with the classical style during this era were not surprised to watch Fisher assume his place atop the standings. He had been in the hunt previously. The ’09-’10 season was supposed to represent the beginning of a pronounced run, which is quite something to say considering the allotment of skilled competitors who occupied 74 kilograms at the time.

Then ’11 happened. After making his second-straight World Team, everything changed. There wasn’t a whole lot of innocence left for Fisher by then, anyway; but whatever innocence remained was vaporized when he fractured his ankle less than a week before the World Championships. The injury? That eventually healed. It was everything both during and after that resulted in scars much longer than the one adorning his lower-most appendage. Jaded and disenchanted already, Fisher’s perception of the US program had no choice but to darken even more. The joy of competition? All that striving for glory and “we’re all in this together” jingoism that is supposed to define World-level athletes? Gone. Bombed and dusted.

The proceeding years saw Fisher hang around. He was too good to all of the sudden just become relegated as a non-factor. He still threatened, was still in the proverbial hunt. But it was also over. He had nothing left. Fisher’s mind was exhausted, his heart had been broken and never repaired, and exasperation became his go-to emotion. It is virtually impossible for any wrestler worth their salt to compete under those circumstances. The ceiling had finally dropped, the floor crumbled beneath his feet, and he needed to walk away if only to cling to his sanity.

He just couldn’t put himself through it anymore.

Two calendar years passed before Fisher stepped back onto a competitive mat. He was a different man in the spring of ’18. He had clarity. Wrestling was, is, seen as an escape. No stakes of which to speak. Fisher was focused on finishing his Doctor of Chiropractic degree from the University of Bridgeport School of Chiropractic in Connecticut (he graduated this past spring). Training, lifting, competing — even the tiniest thing such as tying his wrestling shoes, all occurred on his terms. No taskmasters. No politics. No anxiety over the thought of having to abide by someone else’s idea of who he was supposed to be and how he was supposed to prepare. For the first time in nearly a decade, Fisher was just happy to be a wrestler.

Except he was a different man in December of ’19, also.

At the most recent US Nationals, aka the last Senior tournament contested on American soil some nine months ago, Fisher arrived as the tenth seed. He was thrilled. His opponents, not as much. The then-35-year-old, looking sharper and stronger than athletes ten years his junior, faced little resistance en-route to a finals appearance few saw coming. All of the Fisher-esque signs were available, sans the former surfer-style mop with which he had once been associated. Each and every exchange betrayed a renewed sense of conviction. Forget the reverse lifts, or the headlock that victimized National Team member Peyton Walsh (Marines). The real problem for the field was that Fisher seemed to know something they didn’t, and wrestlers don’t relish having puzzles to solve, particularly when a puzzle comes in the form of a guy who very well realizes how to appropriately attack an Olympic Year.

The pursuit of the 2020ne US Olympic Team is Fisher’s mission as of today. He is a licensed doctor of chiropractic working in and around Denver, fitting training in whenever possible. Which is to say, as much as possible. And this is all nice, it is all important, but it is also trite. Of course Fisher has his eyes on making the Olympic Team. You can’t get more obvious than that. It is a rhetorical concept at the moment. There’s more to him than that hyper-concentrated realm.

Yes, fine, sure: is Fisher supremely focused on giving it his best shot to wind up in Tokyo? Without question. But that misses the point. It’s not what he is trying to do, it is how he is trying to do it. Every breath he inhales from now on is God’s call. No one else — not in Colorado Springs, not in Corsier-sur-Vevey, Switzerland — has a say in his next step. And all that is going on right here is a picture of what that entails, and why it matters.

And all Fisher asks is that you simply try to understand.

5PM Interview with Jake Fisher

5PM: In 2018, you said prior to the US Open that you were basically taking it day-by-day, or event-by-event. You competed at 87 for the Nationals, took 7th. The Trials were next and after a loss in the first round to (Terrence) Zaleski, you ran the table through the consolation bracket, avenged that loss, and wound up a win away from a National Team spot. Considering how you viewed your returning to competition at the time, were those two tournaments impactful enough for you to keep going based on result — or a simple love for competing?

Jake Fisher: Those two tournaments were not results-driven. It was more that I liked the sport again. I was really burnt out after 2016. Even ’15, just being in Minnesota for those four years. I took the time off and just on a whim I’m like, I am going to compete again. But at that tournament (the ’18 Open), honestly, I was taking it event-by-event. I did okay there, but then I was like, Well, I’m not going to the Trials; and then obviously, I went to the Trials. I did pretty well there. For the Trials I thought, I’m kind of out of my weight class, so I’ll go down a weight to 82. You know, put a little effort into it training-wise, and it’s also what I should be weighing.

I think I did a week out in Northern Michigan. (Andy) Bisek let me come out there and he put me up in the dorms. I did a two-week camp before Trials at Curby 3-Style. It was more of the emotional drive why I continued the following year. Because, I had fun at this tournament. I wasn’t under anyone’s money, I wasn’t under anyone’s control. It was just me going out and wrestling. If I wanted to wrestle, I’d just wrestle. It was my choice. I wasn’t enslaved by sponsorships or programs, or anything like that.

Then the next year I was pretty busy with school. I was lifting. I don’t call it “part-timing it”, but I couldn’t get on the mat for a while. Anytime I visited Curby 3-Style I would wrestle Joe Uccellini. I would do that once or twice or month. April came and I said, Okay, well, I’m not going to go 87. I’ll go 82. I trained maybe a little bit for it. I mean, I was pretty neck-deep in school. It was time management. I was really more worried about earning A’s and graduating with honors than I was with winning a US National title — but I did really want to wrestle because I knew that it was a passion.

It wasn’t about the money, the program, or anything like that. It was, I want to get on the mat and wrestle. I was going to enter the Trials but it was during my finals week at the end of my third year of chiropractic school. I was like, Yeah, my career in chiropractic takes precedence and I’m not going to ask my professors to prolong my finals week, because I had about 12 different final exams and practicals. Plus, it was a short turnaround. The Trials were in May, so I was like, Okay, I’m not going, right? I wanted to, but I wasn’t mad about it. It was, I can’t make it, no big deal. I had fun at Nationals. I felt great. Got back on the mat. Didn’t train a ton for it, but it was nice to be back on the mat. It was like a kickstart for the rest of the year. It was just, I still love wrestling, and so I’m doing it.

I knew I was going into my last year of chiropractic school. In that last year you start in July and go all the way to the following May, which was this year. But it was all clinic-based, no classes. I also knew that I had Mondays off and I didn’t start clinic until 12:00pm. It was a 12:00pm-6:00pm type of situation. I knew that I had some more time to actually train. Coming into the Olympic Year I thought, If I am wrestling this year, I’m not going to half-ass it. I am going to put effort into it. And by “effort”, I mean training smart, enjoying it, and not being stressed about wrestling. Money wasn’t an issue, things like that. I was in clinic.

But things had to happen. One was the time, and I had the time — though not the time these younger wrestlers have. But I had the time to squeeze in training sessions. Specifically wrestling, because I could lift on my own. The second thing was partners. I wondered what I was going to do about partners if I really wanted to make an Olympic run in 2020. I could obviously go up to the Curby Training Center and wrestle with Joe. There are limitations with that but it’s a good situation. I have good sparring partners and I do the work, but there are limitations as far as par terre and things like that. When in doubt, I could always spar with him. Kevin Lozano, too. He’s a former USOEC guy, a top-4 guy back in the day. He’s still in decent shape and he got in shape for me.

I knew that there were two partners, but I lived in Connecticut and Joe lived about two-and-a-half hours away if I’m speeding. That’s a five-hour roundtrip and I could train there if I ever go up and visit, but that definitely was not going to cut it. I knew that Alan Vera was in Hoboken. I was in Connecticut, and the Metro North goes straight down to Grand Central. I could walk a mile to 33rd (Street), hit the PATH up, $30 or whatever. It’s worth it. I called Alan and asked if he wanted to start training together. So we began training together at the NYCRTC twice a week in July of 2019.

That was July and August a year ago. When Vera was at training camps in Colorado I would go up and wrestle with Joe and Kevin. I was like, Alright, I think I can do this, make this Olympic run. By September, I said, It’s on. I started 100% training. Well, maybe not 100%, but the intent was there. I was doing it. I found ways to travel. Hoboken wasn’t close, either. It took me two hours and 15 minutes to get down there. But I had the time. I’d get up at 5:00am, get on a train, and get there by 9:00am. We would finish up a little after 10:00, and then I’d jump on another train and make it back in time for clinic somehow.

5PM: Also around that time in ’18 you had intimated that you liked the idea of same-day weigh-ins. Now that you’re back into the weight range in which you spent the majority of your career, has that feeling changed at all?

JF: Oh, absolutely not. It’s even better (laughs). I love same-day weigh-ins, scratch weight both days. For Nationals this year we put together a plan. I dug into some research on what would be the best way to bounce back. I’m 36. I was 35 then. But at 77 kilos, we wrestle first because it’s usually the deepest weight as in quantity of numbers at the US Open. So you’re usually first up, and you want to warm up about an hour into it. I had to figure out a way to do it smartly. I think I was probably weighing around 200 pounds in July. I was training with Alan, which was good because I was heavier wrestling with him. I was about ten pounds lighter than him, but it was good.

The weigh-ins were great. I stabilized my weight to somewhere between 180 and 185. Then I did a mock setup before Nationals where I made it with a two-kilo allowance and wrestled an hour after that. I wrestled a practice, but not a normal practice, because my plan is a lot different from any of these younger guys’ under the program. But I was wrestling with Jon Anderson, so you can imagine how high-paced some of the go’s were. We did a little test based on what type of food I’m eating, what my bounce-back time is, and what we’re going to do for the Nationals. I liked the weigh-ins. The Nationals was good. I had no problems bouncing back because of what I knew about the body and nutrition, exactly what I needed to put back into my body, and how hydrated I needed to be. Timing was everything, as well.

Normally, I wouldn’t have done this, which is insane to me because there is not a lot of education about it. It used to be that I would go through a tournament and just not be hungry. Right? You go through a match, you’re wrestling, and next thing you know, you’re wrestling again. You’re up and you’re down, you’re up and you’re down. I was just never hungry throughout the day, and it’s like, how detrimental has that been to my performance over the years? I wish someone would have been right by my side just handing me food. Like, Here, eat. I think that is one of the biggest things I enjoy about the weigh-ins, too. I actually know that there is plan after every match with what fuel I’m putting into my body, when I am putting it in, and how much hydration I am putting in. Right now, I am weighing 185 and stabilizing right there. It’s good.

5PM: This space in your career is an interesting one because it’s a completely different station in your life, and like you said, your chiropractic career has been a priority. Is there an advantage for you being so busy with something outside of the sport during this stage of your life?

JF: Absolutely. I am not under a regime or a program that dictates when I wrestle, what time I wrestle. And money-wise, my financials. It was more of, I can go do my thing. Like a hobby, and “hobby” in the sense that elite athletes don’t have hobbies. Right? We’re playing chess, we are trying to win. So I use “hobby” loosely, but it lets me not think about wrestling. It wasn’t on my mind all day, as opposed to when that is all you do, wrestle. And that’s it. You’re in the program.

Even at Northern Michigan, it was more wrestling-based. The #1 thing was wrestling, and everything else was coursework and classes. But yeah, I guess that is kind of an advantage for me. I’m not under anything. I owe nothing — to anybody. At the end of the day, if I don’t want to step on the mat, I don’t have to. My finances don’t take a hit if I don’t step on the mat. I can walk away at any point in time and there’s no regret. I enjoy doing what I do, and that’s good. I find the time for it because it is that enjoyable. At this point in time in my life, it is enjoyable. Prior, it wasn’t, like from ’12 to ’16.

But yes, I go do my job and then I do my hobby. But again, when I say “hobby”, it’s not like a normal person’s hobby.

5PM: What is married life like for someone who is competitive, especially since you weren’t a married person in your 20’s?

JF: It’s great, actually. Pretty much, I put it on the table and my wife has been great about it. She knows wrestlers, to begin with. We were dating for a long time. We got married, and then when I said that I wanted to make a run, she was very supportive of it. If she wasn’t supportive of it then I definitely wouldn’t be doing it. It would take a lot out of me to not have her support behind me.

I mean, I’m getting up at 5:00am and getting home at 9:00pm. This past year, it was one of those things where she wanted to see her husband but she knows the goal. I think she understood how passionate I was about it. Because, what kind of crazy person takes a train down to Hoboken that takes two hours and 15 minutes, then takes the train back two hours and 15 minutes and goes to clinic? Just all this traveling? I would do day trips up to Troy, New York and Curby 3-Style, wrestle for an hour, and then drive straight back. She understood the passion that I have and is fully supportive of it. I’m not saying that she likes not seeing me, though I’ll let say that herself (laughs). But she is on-board for this Olympic Year that continues into this next year.

5PM: What was the catalyst for your move out west to Colorado Springs?

JF: The catalyst? I graduated in May. Usually you start looking for jobs prior to that, but COVID hit, and obviously the Northeast got hit pretty hard. All of these chiropractic businesses took a hit and they weren’t hiring. I had to expand my search for a job and I didn’t have much time. It’s like, Welp, you have no money. I asked my wife where she would want to live, obviously. Colorado was on the list and I started searching there. Phoenix was on the list, too. Other places were on the list, but definitely Colorado because I know a lot of people here. That is always nice, to know people where you are looking to work.

I started applying and found some pretty bad job listings. Not the right fit, things like that. I was just combing through jobs, like, I’ve got to find a job, got to find a job. One night I saw a job posted in Denver. It was sports-oriented chiropractic. I looked at the job, looked at their website, and I was like, Oh yeah, I’m 100% applying here. I heard back the next day.

That’s pretty much it. I’m out here now. There are no jobs out there for me in the Northeast. I guess in the back of my mind it was also, The Olympic Trials are next year. How am I going to train where these jobs are located? So it was Colorado. Obviously, I was leaning towards Colorado. I love it. My wife likes it, too. I brought her out here the past three years and visited with Cheney (Haight) and his wife, and she loved it. I brought her here during the winter and we went up to the mountains and did some skiing. I also brought her out here for the summer and the fall, and she loved every season. She was 100% on-board, and luckily, her job is flexible and she can work from home.

5PM: How have you been able to wrestle around and do anything during quarantine?

JF: When I first moved out here I was looking for a place to train. Obviously, the Olympic (& Paralympic) Training Center is shut down, or closed, or whatever. They’re not doing the contact. Then I hit up Joe Betterman and he started doing practices , and I started training with Cheney once a week. I was training with Cheney and a few people who I won’t disclose at this moment. I’d wrestle around with Betterman, as well. He’s weighing about 170 (laughs). He still has that muscle memory. He is actually in pretty decent shape. It’s good because he gives a different look. He’s shorter. Betterman has turned into one of my coaches and sparring partners if needed. That’s definitely a new addition to my routine. Cheney, as well.

5PM: Do you look at your time at Northern under Ivan (Ivanov) as maybe the most recent golden era in this style for the US?

Jake Fisher: I wouldn’t call it a “golden era” but I do believe it was moving in that direction. It’s a shame that he is not coaching. It’s as simple as that. Northern was supposed to be a feeder program, a developmental program. But it turned into a World-class program and it was dismantled by suits, basically. It’s a shame that happened. There are just so many stories I can tell about Northern.

There is no one as smart or intelligent when it comes to coaching as Ivan is. Nobody more athlete-centered than Ivan. He was creative. He knew his athletes — and I’m talking about the first generation of athletes, anyone who came in between ’01 and ’04. I would call them the first generation under Ivan at the USOEC. He brought a lot of structure. He actually cared about the athletes. I mean, he would go home and think about why a bad practice was a bad practice. He was… I don’t even know how to put it. He is the coach more coaches need to be in the US. He really is.

I remember walking into the room and he would know just by looking at you — without even asking a question — he knew what kind of mood you were in. And he knew whether we were going to warm ourselves up, as in a group warm-up; or if he was taking over the warm-up and things were going to become a little more intense. It was definitely the start of what could have been a golden era, and if he were still around I truly believe that there would be better coaching and more medals. But unfortunately, that didn’t continue.

5PM: It’s not just Northern people who feel this way, others on the periphery do, too, that Ivan’s departure from the school was perhaps the worst decision in the history of the US program. You’re going to come at this with some degree of bias I would assume, but do you agree with that consensus?

JF: (Laughs) Yeah. I mean, absolutely. Without a doubt in my mind, and with 100% bias (laughs). Yes, there is no coach like him. And no one even strives to be. The only people who understood were those around him from ’02 to I’ll say…’08? That first-gen. If you weren’t one of the first-gens, then you have no idea what he was about, and it continued. The passion he had. The guy would stay for hours afterwards if he had to. It wouldn’t matter.

Ivan was so technically-sound in everything, not just in what he was good at. He knew the principles behind every move you can think of in Greco. He could teach you the principles of every move and he would let you be creative within those principles and how you would score from it. He would teach an arm drag. Now, obviously the setup is important; the arm has to cross, and in between that and how you get to there is creative. How do you actually arm drag? Are you just going to drag the arm? No, it has to be explosive. That’s another principle he taught. Not like one of these freestyle arm drags where they’re just drilling and it’s like, That’s not going to work. He knew that you had to hit it 100% and be fast and explosive, come across the body. Those are principles. After that, it’s going into the body and into the hips. That was how you were creative. Everyone is different. Every arm drag is different, so you have to be creative with it.

It wasn’t just the arm drag, obviously. He knew the principles to everything. Reverse lift, straight lift… He knew that with a straight lift, no matter what, the first thing you had to do was stop him from moving, and you had to get your lock. That was one principle, you had to get your lock. And then after that, stop him from moving. How are you going to stop him from moving? Then the timing of you stepping up to lift, and that guy defending you because you released the pressure. You step up, you lift, and from there it has to be a throw. He let you be creative between the key principles behind a move. No one even really understands that, but that’s how he taught.

Most coaches, you see that they are good at these certain things but they don’t understand the principles behind what they know. Yeah, I know, maybe it was the background Ivan came from, the Bulgarian system. He could do a reverse lift, he could do a front headlock, he could do a gutwrench. He could do all of these things, but that wasn’t necessarily his move.

He was definitely a top coach. If we’re talking about that era, if we’re talking ’07, ’08, I would say that he was probably a top-5 coach in the world at that time. He was probably ten years deep into coaching and starting to figure out how to really excel as a coach who is athlete-centered and driven, creative. And he was smart within the wrestling world. I think that’s what it takes.

5PM: The circumstances surrounding Ivan essentially being forced out, how did you — personally, competitively, emotionally — reconcile how this would affect you? Just plainly speaking, how did it affect you?

JF: Well, I haven’t made a Team since being under him, so I would say that it has affected me quite a bit. It was a tough thing, I think, with the coaches in his absence.

Like in Colorado. I was in Colorado for a year, year-and-a-half during the 2011-12 season until the Olympic Trials and I had a new coach, Momir (Petković). I mean, he’s a high-level coach — but he didn’t know me. And he had a bunch of young guys there who were between 18 and 20-years-old. He just didn’t know. I could walk into the room and he would have no idea what I’m thinking. I would walk into a room with Ivan and he would immediately know what I’m thinking because I was with him for eight-and-a-half years.

It was a tough battle being coached by other people and trying to explain to them what I need and how I’m feeling physically. And, a lot of them didn’t listen like Ivan. That’s when I came to realize that a lot of these coaches, they’re not athlete-centered. They don’t listen to their athletes and then they blame performance on mental toughness. It’s disgusting. The best thing is that I was a #1 guy at that point and the coach doesn’t even listen to you. It was like, You’re the National coach and you’re not even listening?

It’s disgusting. They just think you’re not mentally tough enough if you express how every week around Thursday — because we had gone seven mat practices by that point in time — that you cannot do that because your body is starting to break down. But every Thursday, you realize — even though the coaches haven’t yet — that you get these minor tweaks and that by Friday you can’t wrestle because your back is tweaked, or your knee, shoulder… Something is hurting and it takes away from Friday, both practices. Then it takes away from Saturday, maybe even that next Monday.

They don’t listen to their athletes, or they didn’t listen to their athletes, and they blame it on mental toughness. Oh, you’re just not tough enough. It’s interesting. It is a struggle, I would say. This is bringing back memories right now. It was definitely a struggle after Ivan, finding the right coach, and I still haven’t found the right coach besides myself and some advisors who I put on my team that I can just call, FaceTime, or whatever. I have like, five now who I can bounce ideas off of (laughs). Some double as sparring partners, so it’s great.

Now I am 36 and understand a lot more wrestling-wise about what I need. Athlete-centered-wise, I am pretty smart about things and understand how to train someone, and how to train myself. Obviously, I am always going to get opinions from who I call my advisors, staff, whatever you want to call them. It has been great, actually, not having to introduce a new coach into my life who has no idea who I am or what drives me. I have a slew of USOEC first-generation athletes on the coaching staff for me who double as sparring partners. They know me. They have known me since around 2002-03. They understand what drives me and they guide me pretty well. There are of course a few other people on my staff who I can call up, like Jack Conroy from Green Farms Academy. I coached with him and he was in my corner all through the Nationals. Scott Honecker, who coaches at Williams College in Massachusetts. He’s also an advisor. He is a ref and helps me out with the rules, strategy, things like that.

So yeah, it was a struggle from the time Ivan left until I started back up in 2018 (laughs).

Ivanov (left) provides Fisher with instructions in between periods at the 2010 World Championships in Moscow, Russia. (Photo: Tony Rotundo)

5PM: In 2010, you earned the right to represent the United States at the World Championships after having already spent a good deal of time in the sport. What did it mean to you?

Jake Fisher: (Laughs) What a terrible question.

5PM: I have to ask this.

JF: I know, I know. What did it mean to me finally making my first World Team?

5PM: Yes, please.

JF: Okay, how do I put it? I didn’t really reflect on it because I was full-steam, I’m going to get a medal. Making that first Team in ’10 was like, Alright, this is the start of something good. Looking back, it was, I’m going to win a medal. I’m going to beat all these top guys in the World. But right now what does it mean? I still don’t even know. It was great. It was a start. I was with Ivan, it was the first Team I made, and then it ended abruptly the following year.

It was good. I don’t know much else to say about that one because I wrestled one match against the guy who took bronze (’07 Worlds, ’08 Olympics), Christophe Guenot. I lost to him, and then after that I went to Colorado. I had been in Boise (with Ivanov) and went to Colorado last-minute. I ended up making the Team in ’11, and that took me into the five days before the World Championships. We were in Greece in the training camp playing handball and I suffered a Lisfranc fracture/dislocation. I didn’t get to compete from then on and it just turned into a downward spiral, I guess, of not competing well. So yeah, I don’t know. I don’t know if that answers your question.

5PM: I was going to ask about 2011, anyway. Might as well cover the whole situation.

JF: It was five days before the World Championships in Istanbul, Turkey. We were playing handball and it was a fracture/dislocation. What was interesting is not that I didn’t compete, but rather how the organization, as in USA Wrestling coaches, handled it. I went and got x-rayed immediately, it was fractured. And then they were like, Can you compete? They brought in the doctors and came back saying it wasn’t good. I’m like, Alright, and my foot is the size of a basketball. It was just so swollen. I’m in pain but I kind of want to still wrestle. It is also 2011, which means that we have to qualify the weight (for the Olympics). So, unselfishly, I’m like, Maybe we need to have someone else wrestle, because as of right now, I can’t even fit my foot in a wrestling shoe. The trainer was there. I iced. It was excruciating pain.

I was literally in nonstop pain for two days in Greece and then we left for Istanbul two days later. The swelling kind of went down. I had no calves, just nothing at that point in time. I was just crutching around with no protection. We get to Istanbul and we’re on the bus outside of the hotel. They come to tell us that our room is ready and they say, “Oh, Jake, you’re going to the training partners’ hotel.” I’m like, What? Why? I just remember Dennis Hall saying, “What the f**k?” I was like, Seriously? They said “Yeah”, how it was something about the financials and how they can’t afford a room. That’s what Mitch Hull, (Steve) Fraser, whoever — one of the suits — told me. They couldn’t afford another room, or even a cot for one of these large Istanbul hotel rooms. And I saw them. By the way, the trainer is staying at the hotel with the Team. So it’s like, I’m still on the Team — why am I getting shoved to the hotel with the practice partners?

Then I take the bus several miles away to a different part of Istanbul. Not a very good part. I get there, and I’m a pretty tough person so it’s just, Whatever I’ll self-medicate. We get to the hotel, there’s no elevator, and I’m on the third or fourth floor. I had to crutch up every floor. There is no ice in the hotel, no trainer in the hotel. I have a Lisfranc fracture without any protection around it. I have crutches. I’m hobbling on crutches up and down the stairs at the hotel. No ice, no trainers. Just nothing.

Fraser was telling the practice partners — and me, now, obviously — that we can take a train from the hotel to the venue and that they would reimburse us for the train fees. And I’m just like, We’re a mile away and they don’t even care. They don’t even recognize that I am on crutches with nothing around my ankle. It’s swollen, it’s painful. No trainers, nothing. They just disregard me and I have to crutch a mile to the train to get to the venue to watch. They don’t even realize it. I did that the first day, crutched a mile. I did that around town, too. I am in pretty good shape, about ready to compete. I’m probably in one of the best shapes of my career and ready to win a medal. I’m really peaking. I’m in really good shape just crutching around. I’m pretty athletic (laughs).

We get to the venue and there’s Fraser. He asks, “How’s it going, how’s the foot?” I mean, he doesn’t really care, right? So I’m looking at him and he goes, “You look mad.” I said, “Yeah, I have to crutch around. What do you mean?” He tells me that they will pay for my taxi back to the hotel, that they will reimburse me for the taxi. I don’t have any cash on me. He says, “Okay, we’ll get you some cash.” Just completely disregards everything, right? I’m fending for myself in Istanbul, on crutches, no protection on my foot. I am in pain. I had to ask someone for prescription medication because I was in a lot of pain. Not a medical person, one of the other athletes. I took painkillers, and it wasn’t good. That whole trip was pretty bad.

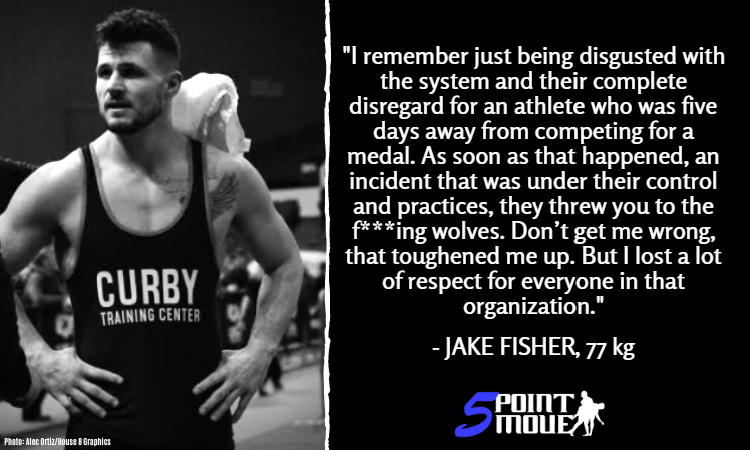

I remember just being disgusted with the system and their complete disregard for an athlete who was five days away from competing for a medal. As soon as that happened, an incident that was under their control and practices, they threw you to the f***ing wolves. Don’t get me wrong, that toughened me up. But I lost a lot of respect for everyone in that organization.

Finally, one of the trainers had a boot sent so I could protect the leg for the five or six days of the tournament. The swelling had gone down. I remember just thinking, Now I have to get surgery. We get back to Colorado, and immediately I go to the sports medicine department and they put me in contact with a surgeon. I had surgery within a week. After surgery, two or weeks later, I’m at the OTC but just going to sports medicine.

There were these athlete performance reviews that they were doing back then. I’m in a meeting with Fraser and Momir. It was October. They are just asking me how things are going. I walk into the meeting basically ready to beat the sh*t out of these two. They’re like, You look angry. I just went off, telling them what they did. Then it becomes, You have to understand our budget. They just blamed it on the finances, again. I’m sitting there disgusted with everything they had to say. They told me that they couldn’t afford a room for me. So then I’m like, Those rooms were extremely large and you could have fit a whole nother queen bed in those rooms. Why couldn’t we have just rolled in a cot? You know, for the #1 guy who is injured so he could stay in the hotel. And then it’s, Oh… Maybe we made a mistake. Like, We’re kind of sorry. They could tell I was so pissed about that. They apologized again. You could tell it was condescending.

Next, the question was, Well, do you believe in our system? And I look Steve Fraser straight in the eye and tell him, “F**k no.” There’s a little shock in his face. He goes, “Well, at least you’re being honest.” I then give him my spiel about Ivan’s system, and I tell them, “You guys haven’t listened to one word I’ve had to say since I’ve been here, about training, about anything. Why would I believe in your system? You don’t listen to the athlete.” I’m telling them all of these details and they’re like, You’re young. You can go through this training. I was 26 or 27 at the time. I’m just like, No. No. They just didn’t get it.

That was Istanbul 2011. It sucked.

5PM: The US program is not a state-sponsored one, so there are often different voices all screaming different things at the same time. Do athletes have to consider unionizing? In other words, if there are cases of distrust, perceived disloyalty, what is the recourse? How does that get fixed?

JF: Well obviously, the first thing you need to do is eliminate the suits, and by “suits”, I mean USA Wrestling. You have to get them out of the picture and develop the program without having their support, as in financial support. Most athletes right now, and I remember being that same athlete, they are financially driven. They are like, Wow, I’m the #1 guy. What does the #1 guy make right now? $1,000 per month? You can do better than that, and have a better life than that. That’s nothing. That’s poverty, and they enslave you into this poverty. It’s disgusting. Go do what you need to do in life and train.

There are ways to do that. There are a handful of people who do help you out. Yeah, you need structure, and there are programs for that. You go to Northern Michigan with Bisek, things like that. But after that, if we’re talking after college, go do what you need to do. You have time after that to train and find the right things. Don’t limit yourself with a program. Programs are setup to be generalized. Most programs in the US are generalized, unless you’re looking at the RTC’s (regional training centers) for freestyle. Those are specific to each athlete and their model is great. They get results, and if you are an RTC athlete, they focus on you. Look at all of these other programs and they are all generalized. Why would a heavyweight need the same training as a 60-kilo guy? Why would they even do the same practice? It doesn’t make sense to me.

Yeah, there are times for generalization and development, and that starts either in high school or going into the program. You eliminate the fact that these programs, these sponsors, are enslaving you into becoming unable to do what you need to do. You don’t know where your next paycheck is coming from. You are training to make an Olympic Team, to win medals, and you’re enslaved by your sponsors. You are. You say one wrong thing or have one bad performance, and they can just nix it right then and there. You are under their control.

I advise any of these athletes to find what they are going to do in life and to pursue it — and wrestle, as well. Find the right situation. You can find it. There are certain things you can do. You don’t have to train this way. You don’t have to do 11 workouts a week. You don’t have to be on the mat eight times a week. You don’t. It’s insane to me, this idea that more is better when it’s not. Especially when it comes to development. You find the time. Yeah, you can do a two-and-a-half hour practice with an hour-and-a-half of technique, but that’s one practice. You don’t have to come back later in the afternoon for two hours of live, or whatever it is. You don’t have to do it.

The system is not great. Like I said, it starts with the suits and then it becomes the coaches. The coaches have to get better. The fix is the coaches. They cannot be driven by popularity. And you see all of these little things popping up, like the athlete summit, the Greco summit, the GRIT thing, whatever that is. I don’t know the specifics of these things, but it’s like you get this handful of coaches who think they are Greco coaches. They go to these summits and then it’s, Whoop, I’m a better coach now! I don’t think that’s where it’s at.

They get on these Zoom calls and have meetings about meetings, and they talk about how we can improve Greco? You know what? Get off your fricking phone call and start brainstorming. Let’s get creative. Let’s start watching film and really start dissecting film. Let’s start thinking and picking people’s brains. Where are the coaches like Bill Belichick? I hate to throw the Patriots head coach out there because they always win, but he wins. Right? He’s smart. He is athlete-focused, everything is about the individual. He’s a good coach. I mean, Phil Jackson. Creativity. Management. How do you manage athletes? No one is managing these athletes. Failed project after failed project. It’s insane to me.

When Fisher caught fire at the 2019 US Nationals, ’18 World Team member RaVaughn Perkins (NYAC) was among the vanquished. Fisher prevailed via 9-0 tech fall before dropping a 5-1 decision to Kamal Bey in the finals. (Photo: Richard Immel)

Coaching-wise on the Senior level, how do you mismanage one of the most talented, athletic people in Greco in the world? Kamal Bey should have three Senior medals by now. And he doesn’t. How do you mismanage that as a coach? It’s insane to me. Tracy (G’Angelo) Hancock. Athletic. He had to go to Norway. He had to return to Norway a year after beating Olympic champs. That says something. What have these coaches done? He had to leave and he got so much better. It’s insane to me how non-intelligent and not athlete-centered we are towards the individuals for the level on which we compete. We are the top guys. It’s insane to me how bad it is, how badly we are mismanaging athletes.

Every athlete is different at this level. You have to take into consideration their anthropometry, their body structure, how you train them, and what their weaknesses are. There’s no creativity, there is no intelligence in most of these places. I can’t say that for development because I know that Bisek is doing a great job at the USOEC and he has his hands full with them. He’s putting out some good guys and he is developing some good guys. But after that, what do they do? Do they stay the same? I don’t know.

It’s lacking. I feel like it’s a problem that can be fixed if these coaches get better as coaches. And I don’t care how you do it. Obviously, I’ve had a few coaches, so maybe I might understand it a little bit better. I have been coaching, as well. I am understanding it a lot better now than I did ten years ago, which is that it lies with the coaches. That is something I understand now, just having the epiphany that it really is the coaching. We are limited by the coaching in the US for getting medals. We have the quantity of athletes for Greco. They are quality, also. There are so many athletic guys. They just need the right coach and they are winning multiple medals. But it lies with the coaches. That’s the fix.

I am going to do my part when I’m done trying to win a medal this next year. Hopefully, I’m smart enough. Realizing this drives me to be a better coach. I coached high school the past few years and I’ve grown a lot between being an athlete and a coach. I think that I realized a little bit better regarding how we can improve at coaching, including myself. Because, getting coached by bad coaches is probably the best thing that has happened to me in my coaching career. And really, also my athletic career, since I know what to do now.

5PM: Greco is always in a weird predicament because on one hand, people feel that the style and its athletes aren’t treated fairly — but if anyone speaks up it is often construed as whining. Yet if no one says anything, then it is Greco getting pushed around. Why is this a no-win situation?

Jake Fisher: You have to change the culture, if that is going to change. In the US, I don’t think that is going to change at any particular moment. You know, we can promote Greco as much as we can. I think getting content out there is good, but real content. I think it just lies with the athletes and the results. It’s about changing the culture and it is very hard to change the culture, especially with both styles.

As simply as I can put it, it is just a cultural thing. You go to Russia, you go to all of these other places, and Greco is the top sport in the country. Everyone knows who you are. I think that it would take a long, long time. Our focus shouldn’t necessarily be getting the recognition, we should be focused on getting the results, then getting medals. And stay humble. Yeah, we’re not getting paid the way freestyle is getting paid. So what? You’re dealt the cards you’re dealt with. I think if we get more results, medals, then more medals, then maybe we start having more things to talk about and more people start jumping on board. It starts with getting medals, and getting medals starts with athletes performing. And athletes performing starts with great coaching, and great coaching starts with coaches doing their jobs.

5PM: Was there any extra satisfaction involved with your run at the December Nationals?

JF: I want to say that it has kept me going this next year because I know, that with the system I devised for myself with my advisors and sparring partners, that I can definitely win a medal at the 2021 Olympics.

5PM: Okay, but it’s not that you merely advanced to the final, it is also who you defeated on the way there, and the manner in which you did so. Did you feel encouraged as soon as you started moving forward the way you did in that tournament?

JF: It was fantastic when I got there because I guess I was in a good situation. I was the tenth seed. That is a fantastic seed. I don’t think I’ve ever been seeded #10. I was like, This is amazing. I’m about to make a splash. I come out first match, wrestle, and then after that I kind of got on a roll.

I got on a roll that tournament because I knew that these 77-kilogram guys haven’t been around the block too long and I was in pretty tremendous shape. My weight was great. All of the chips flew and I was just having fun. I mean, that’s what it came down to. I enjoyed the process leading up to that tournament. Like I said, it goes back to who would travel for two and a half hours to work out, train for an hour, and then drive back? I enjoyed the process. You have to be able to enjoy the process to be able to even do that. I hate to say that. It’s what everyone says, Enjoy the process. Like, Hey, you’ve got to enjoy the process! But I don’t think I ever quite enjoyed the process like I did last year leading up to the Nationals, and the Olympic Trials, as well, because we were definitely prepared for the Olympic Trials until COVID hit. I don’t think I have enjoyed the process since I think I was in high school just like that.

With Ivan, it was more hard-nosed. It was tough and it built character for myself. But actually having so much fun doing what I was doing leading up until the Nationals and Olympic Trials was probably the best by far in how much I have enjoyed the sport of wrestling. The factors that contributed to that were definitely everyone around me. The support that I had with my coaching advisors, sparring partners. It was pretty special, this past year and leading into this year now. It has already started again and I have added some more sparring partners and coaching advisors, and everyone has been fantastic.

But yeah, leading to the 2019 December Nationals, I loved making a splash and I loved the #10 seed. The lower the seed, the better. I really don’t care. I’ll knock these guys out in the first round or second round. It really doesn’t matter to me because everyone talks about the recovery and the weight cut. Well, I recover within an hour. I really don’t care who it is. That’s about it.

A Fisher headlock was one part of an offensive blitz that helped put talented Marine National Team member Peyton Walsh away in the second round of the 2019 US Nationals. (Photo: Richard Immel)

5PM: The (Olympic) Trials postponement. Was that good or bad?

Jake Fisher: Obviously, I was prepped for Trials. But it didn’t affect me. I wasn’t really mad because I have been in this sport for most of my life. It was like, Well, it looks like it is postponed a year. Fantastic, that means I can get better, do this all over again, have fun, and do my hobby. I kind of was just like, Great. Not “great”, but I get to continue to do this. I think it is a good thing for me because I only trained for five or six months leading to Nationals, took a little time off and trained for Trials, and then I took a little time off and now I’m just getting right back into it.

It’s enjoyable. I still have my career. It is one of those things where this is another great thing in my life and that I can keep pursuing this avenue. And who knows? It is going to be 2021. Who knows if I go to 2024 Paris and try to become the oldest Greco-Roman athlete to make an Olympic Team?

Follow Jake Fisher on Twitter and Instagram to keep up with his career and competitive schedule.

Listen to “5PM40: Sam Hazewinkel and Jesse Porter” on Spreaker.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE FIVE POINT MOVE PODCAST

iTunes | Stitcher | Spreaker | Google Play Music