The most “Olympic” of the Olympic sports, yet largely relegated to the confines of digital media, takes centerstage on Sunday morning (Saturday night in the US) with Greco-Roman rightfully leading the charge.

A week’s worth of action has already transpired in Tokyo. The spectacle that is the Olympic Games, in modern times, leverages its grandeur in order to point a warm yellow spotlight on the iron-willed sacrifices and drippy tales of inspiration associated with virtually every other sport besides wrestling — which to a feverish fanbase would ring just a little less insulting if the exclusion wasn’t perceived as purposeful. But it is. And, again, for however many Olympiads in a row, you simply hope that the masses stumble upon the live stream, even if inadvertently. Our sport, there is not another like it, hence why we want outsiders to at least offer a glancing eye.

We want them to watch wrestling, where physical and emotional turmoil are available on a match-by-match basis at the Olympic Games, but is swept to the side like so much dust on a warehouse floor… Wrestling, the original martial art… Wrestling, the activity begetting of a lifestyle that is so physiologically-challenging, it has birthed a unique subculture replete with endless slogans and self-professed “mindset coaches”. Indeed, the journey is so treacherous that continual encouragement is a perquisite for mere survival, let alone success.

Most of all, wrestling is by nature an odyssey of combative intimacy, and Greco-Roman in particular invites the brand of tension and drama to which newbies can relate if open-minded enough to give it a chance. Here’s hoping that they do.

Team USA in Tokyo

Hitching lifelong aspirations to one tournament is not for the timid, but the daring.

Each of the four US Olympians who will compete in the Tokyo Games have sojourned on different paths over the course of their respective careers. This has been covered. Along the way, they have added skills, honed their styles, and blended it all together into varying customized methodologies which will play a role in their performances.

60 kg

Ildar Hafizov (Army/WCAP)

Sunday, August 1, 11:00am (Saturday, July 31, 10:00pm ET)

Now 33 years of age — and 13 years removed from his first Olympic appearance in Beijing — Hafizov stands as the oldest athlete in his bracket. Rings around the trunk are not necessarily a hindrance for upper-weights, but it is usually different for lightweights. Greco is a speedier game when it comes to the shrimps. Attributes such as agility and explosiveness are especially at a premium for 60 kilograms, and both tend to diminish with age. Therefore, is it unfair for observers to spot the date on Hafizov’s birth certificate and take a pause? Not really.

The problem with that is Hafizov still packs dynamite on the feet, and the pop he can introduce via double overhooks is made all the more effective due to impeccable timing — one arrow in his quiver that has actually become sharpened the past few seasons. Timing comes with experience, something for which Hafizov is not lacking. His preference for high locks from par terre, a prolific weapon in recent seasons, has also paid off for the most part. “Most part”, if only because he has at times watched opportunities to score fall by the wayside.

A prime example would be Hafizov’s bout against Lenur Temirov (UKR) in the ‘19 Worlds. Temirov, who had earned bronze in ‘18, was trailing 2-1 and on bottom PT when Hafizov locked and stepped parallel for a high-gut-lift variation that, for him, normally results in a waterfalling exposure. But the entire operation broke loose on the attempt, allowing Temirov to reverse and convert a crash gut for a 4-2 lead. There are other documented instances of Hafizov missing out on critical scores from PT top, including most recently in May at the Pan-Ams. None of this is to suggest that par terre offense is a weakness of his. It isn’t. When Hafizov keeps it simple, high lock or otherwise, his efficiency is near-pristine.

Summary

At 60 kilos, Sergey Emelin (RUS) is the best from par terre, two-time World champ Kenichiro Fumita (JPN) is the most dynamic, and multi-time medalist Elmurat Tasmuradov (UZB) is the best all-around athlete (depending on the weight cut). ’18 silver Victor Ciobanu (MDA) is the weight class’ workhorse, and Ali Reza Ayat Ollah Nejati (IRI) is the most well-balanced. Where does Hafizov fit in? He’s at or near the top pertaining to technique. Virtually everything he does is textbook. Crisp, classical. He even makes grueling gut defense drip with elegance.

67 kg

Alex Sancho (Army/WCAP)

Tuesday, August 3, 11:00am (Monday, August 2, 10:00pm ET)

One small reason. Then another. And another, and another. Sancho’s confidence arrives in pieces during matches. One might surmise that even the slightest breakaway off of a dissatisfying tie-up teaches him a lesson to which he can adjust and refine for later on in the bout. Sancho enters each tournament with an appropriate amount of self-assurance, but little positional victories are how he really gains steam — even when he does not score. This could be described as a championship attribute, understanding that the miniature battles no one notices are often the most important.

And it is especially important now that he is in Tokyo, where scoring chances on the feet are likely to prove quite scarce. “Buttoned-up” is how to put it. Sancho’s hawkish, angular approach is how he feeds arm drags and slaps around back for go-behinds; or, finds a corner to clamp a body attack. But the latter is not an expectation in this tournament, which is precisely why being “okay” with playing solid position is a strength. In years past for Sancho, it wasn’t. He had a more “open” style, was a little less risk-averse. Sancho will still pounce for scores, but he has matured enough to know when that juice is worth the squeeze.

Provided Sancho is within striking distance on the scoreboard — and isn’t victimized by phantom passives — it is all about his ability to lift. He has an upper-echelon straddle lift that is on par with the bracket’s heaviest-hitters; and though a lift is accompanied by a fair amount of risk, now is not the time to double-clutch and re-think the whole thing. If Sancho is to make the podium, locking, hoisting, and launching is mandatory — regardless of who happens to be the bottom guy.

Summary

Sancho operates with a dash of foreign flavor. Domestic competition compels everyone in the US to pummel their brains out, but the overseas version of Sancho is looser and flings in-and-out of ties as if a half-step away from a throw at all times. His is a personalized, almost eccentric rhythm. It didn’t play well against reigning Olympic/2X World champ Ismael Borrero Molina (CUB) in their two bouts, but Sancho also wasn’t an Olympian then. It’s a new day. Sancho believes he belongs in this tournament and hopefully won’t abandon his most trusty weapon when it matters most.

87 kg

John Stefanowicz (Marines)

Tuesday, August 3, 11:00am (Monday, August 2, 10:00pm ET)

Every step forward… Every hand on a wrist, every forearm wedged against a sternum, has to have a purpose. Creating pressure is Stefanowicz’s default mode. With legs firing like pistons he urges forward, using the appendages of antagonists against them. Earlier in Stefanowicz’s career, this was primarily all he had in his favor. It would not be outlandish to opine that earlier this quad, Stefanowicz was 90% physical and 10% technical. But he has always been tactical. There is an inherent value in keeping it simple, which is what Stefanowicz did until the feel for how he wanted to direct motion caught up with his wealth of tenacity.

Pressure in a match is often subtle, and difficult to interpret from a distance. The position of the legs, hips, and head account for the overwhelming majority of successful mechanics, whereas everything else up top is responsible for getting a handle. Most have witnessed Stefanowicz ram opponents around the mat, but what they miss are the multitude of quick pushes and pulls which force foes to constantly step and re-step. A period is three minutes. After the first :80, or just prior to the ritualistic “pick a guy to go down in par terre” phase, Stefanowicz’s opponents have already been bumped and checked several dozens of times. This allows for a greater number of potential scoring opportunities in both periods, or however long it takes for wear to accumulate.

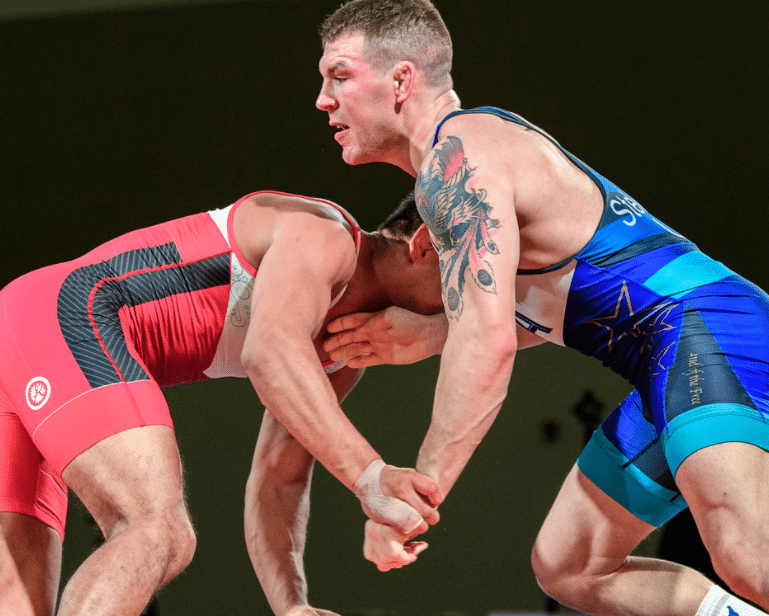

Stefanowicz (blue) walks into the 2020 Tokyo Olympics on the heels of two straight Pan-American Championship gold medals. (Photo: Tony Rotundo)

What Stefanowicz has done to impressive effect is lean on his excellent athleticism and generate meaningful attempts via counter-offensive scrambles, or arm spins which are derived from a reach or step too far due to push-pull-pressure. He is not an easy mark for passivity, thankfully, but bottom par terre — as it is for virtually everyone in America — is a vulnerability. One could look at Sancho and figure that if he can score from top, his odds of advancing skyrocket. For Stefanowicz, it is the opposite. He doesn’t necessarily need to score on top to win; but he absolutely must defend from bottom. 87 kilograms features closer scores. Step-outs are part of the picture (a Stefanowicz strength), but matches are commonly decided by par terre points. If Stefanowicz can remain in the hunt deep into the second — and in between or during come up clutch in terms of defense — he might very well assume control of the narrative.

Summary

“STEF” does not have relevant time-on-target with most of 87’s major players. There was Islam Abbasov (AZE) this past January, as well as the infamous criteria loss to Zurabi Datunashvili (SRB) over four years ago. Whatever the rest know about him is from outside of sanctioned competition. They will not enjoy the introduction. Stefanowicz keeps a very high and consistent pace that is unusual for this weight category internationally. A perilous thought for those who prefer to plod and wait for PT.

97 kg

G’Angelo Hancock (Sunkist)

Monday, August 2, 11:00am (Sunday, August 1, 10:00pm ET)

It won’t come easily. They are not going to dig inside and rest their chins on each other’s clavicles before arriving at some unspoken gentlemen’s agreement to start opening up. If that were the case, you could go ahead and award Hancock the gold right now, for no one at 97 kilograms is a more dangerous offensive threat. And that is an objective statement, not a red, white, and blue declaration of patriotism. Hancock is no longer reliant on a go-to bodylock because Senior competition fails to avail those types of looks. So, as he has advanced in skill the past four years, he has incorporated a healthy number of complimentary ties and entries which provide opportunities for other scoring chances, big and small. It could be a cross arm-drag that forces an opponent’s inside leg to jut forward on an angle, thus creating a natural lane to wrap the body; or a two-on-one that invites an underhook, which leads to an off-balance or a reach-around from the other side once the underhook is cleared — something of a rarity for upper-weights.

Hancock had recently turned 20 years of age when he made his first appearance at a Senior World-level event in ’17. Four years later, the native Coloradan has faced many of the sport’s best in his weight division and, in the process, collected nearly a dozen international medals. (Photo: Tony Rotundo)

He has plenty of options. What’s more, Hancock knows it, and feverishly works with a variety of setups in mind based on the opposition’s movement patterns (which in this weight category, become at least a touch predictable). Unfortunately, this does not make Hancock 97 kilos’ version of Neo from The Matrix. In a normal competition, the slogging is exceedingly tight. At a World-level tournament, it is downright snug. And since Hancock is not a brawler by trade, he is left to wade through a thick brush of wrist-grabs and finger-pulls in order to find the daylight necessary for a meaningful scoring entry. That he is not shy about using his feet and hips to do the talking when topside limbs are occupied is how he breaks off of go-nowhere tie-ups and swims into the more dynamic attempts with which he is associated.

Hancock does not need to take what would be an uncharacteristically physical approach against most of the field. His motion involves more than enough angles and slight deviations in tempo to where he can lead the waltz. But there are a few potential counterparts who might require an alternative strategy. Such as ’16 Rio bronze Cenk Ildem (TUR) and two-time World bronze Mihail Kajaia (SRB). Both are lumbering bruisers and excellent in par terre, but both begin sagging midway through matches because their output is geared towards receiving passive chances, not actual offensive scoring. A “meaner”, more physical Hancock would fluster this duo immensely. Meanwhile, against 97 kingpin Musa Evloev (RUS), Arvi Savolainen (FIN), and Kiril Milov (BUL), Hancock’s patented movement-heavy style would offer a stark contrast to the linear, choppy mechanics preferred by the trio.

Again, he has options. And options win matches in premier tournaments.

Summary

The most pressing “x-factor” staring Hancock in the face is his lack of matches this season. The first minute of his first bout could go a long way towards determining the rest of the tournament, given the role passivity tends to play. Nerves, adrenaline, that first contact…it all matters more this week. More so than even whoever is the one standing across the line. Draws are part of this (Hafizov’s was just released, FYI), but not an all-encompassing item of interest. This is the Olympics. Each opponent poses a problem. Hancock is a strong candidate who needn’t focus on anyone else — not Evloev, Aleksanyan, Szoeke, or Savari — but rather, his own considerable capabilities.

Listen to “5PM50: Mr. Fantastic Benji Peak” on Spreaker.

Listen to “5PM49: Robby Smith on coaching, fatherhood and mentors” on Spreaker.

Listen to “5PM48: Austin Morrow and Gary Mayabb” on Spreaker.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE FIVE POINT MOVE PODCAST

iTunes | Stitcher | Spreaker | Google Play Music