Last week, we released a lengthy exploration into how various metrics for Greco-Roman could be applied in an effort to engage more fans as well as provide coaches with a different perspective when evaluating performance. The piece, thankfully, was well-received and has generated a substantial amount of positive feedback. It should also come as no surprise that one item people have wondered about is what the numbers might read with regards to a collection of current US athletes.

Like Kamal Bey (77 kg, Sunkist), for instance.

Bey is indeed an appropriate case study. He scores. A lot. A real lot. And just as important as all of that scoring is his approach. Bey is an Attempts machine. He has always been this way. It is easy to understand. Simply put, if he is wrestling other humans, he is trying to throw them over his head. This reason alone is why fans love him — and why most opponents do whatever they can to bind his wrists and stifle his dynamic brand of athletic expression.

Although the opening stats proposal was intended mostly for the Senior level (since Senior is the Olympic level, which is where fans are desperately needed in the US), we will spotlight Bey’s explosive run to Junior World gold in 2017.

Why?

The fact that he scored 61 points in the tournament is a big part of it.

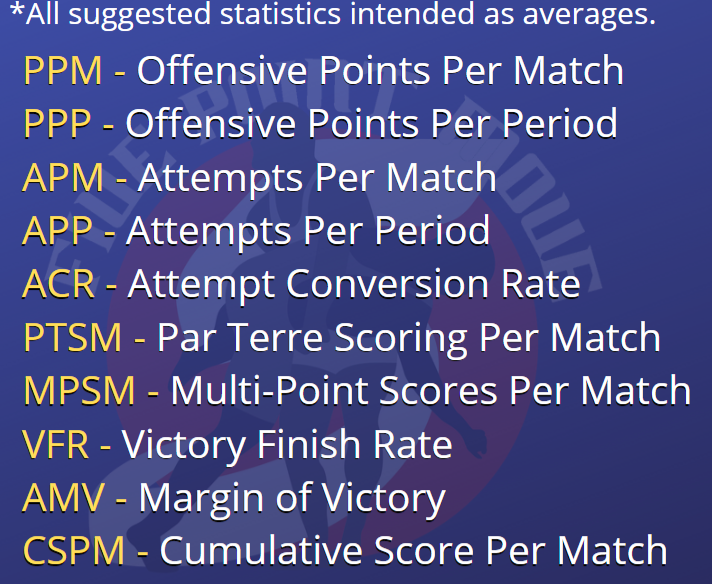

As a refresher, below are the ten statistical categories featured in the original proposal that will be used to measure Bey’s offensive prowess from Tampere ’17.

On the Feet

Points distributed due to passivity, cautions, lost challenges, etc., are not included.

PPM — Points scored from step-outs, takedowns, and throws.

PPP — Average number of offensive points scored per period.

APM — Average number of meaningful attempts per match.

APP — Average number of meaningful attempts per period.

ACR — Percentage of attempts which translated into offensive scores.

Additional

PTSM — Average number of points scored from (static) par terre.

MPSM — Average number of actions which scored more than one offensive point.

VFR — Percentage of bouts ending via fall or technical fall (does not include disqualifications, injury defaults, etc.).

AMV — Average point differential in wins.

CSPM — Average points total resulting from an athlete’s matches.

Kamal Bey — 2017 Junior World Championships

WON Pilkeun Bong (KOR) 9-0, TF

WON Karan Mosebach (GER) 10-1, TF

WON Nasir Hasanov (AZE) 7-4

WON Per Albin Olofsson (SWE) 19-7, TF

WON Akzhol Makhmudov (KGZ) 16-11

PPM: 11.2

PPP: 6.2

APM: 4.2

APP: 2.3

ACR: 2.1

PTSM: 1.6

MPSM: 3.6

VFR: 60%

AMV: 6.8

CSPM: 16.8

We now work to gain some clarity since some of these statistics practically leap off the page and call for pertinent scrutinization.

First and foremost, ordered par terre was not in the rule-set in ’17. If it were, one needn’t stretch their brain all that much to imagine Bey lighting up the arena even more than he already had. His PTSM at the Junior Worlds that year was 1.6, meaning he scored just under two points per match from par terre top. For those who have been following Bey as a Senior, they know that is a laughably-low par terre scoring rate.

Secondly, and this was not enunciated properly in the introductory piece last weekend, a low ACR is a good thing. Bey’s ACR in Tampere was 2.1 — which is essentially saying he found a way to score nearly every other attempt. This is an important distinction. The key to observing attempts is balancing their frequency with effectiveness. A high number of attempts is appraised as a positive attribute because it indicates an active, scoring-conscious competitor. Likewise, if said competitor comes up empty often, their ACR is going to demonstrate such with a bloated number.

In baseball terms, it is akin to “swing-and-miss” rate — with the main difference from an analogous perspective being that most of us are A-OK with swings and misses in Greco because there are sometimes not enough swings.

Inside Bey’s ’17 JR Worlds Output

A PPM and PPP of 11.2 and 6.2, respectively, are ridiculous considering the level of competition. Although these numbers were gleaned from a Junior tournament, it was the Junior World Championships. For additional context: before Bey won his title in ’17, the last US wrestler to triumph at the Junior Worlds was Olympic bronze Garrett Lowney all the way back in ’99. Junior might not be Senior, and in all fairness, it’s not even a close call. But — successful Juniors tend to profile as eventually-capable Seniors, if not stars of the sport.

Production Overview

As advertised, Bey likes making lot of attempts. He averaged 4.2 per match in Finland and only two of his bouts went the distance, resulting in an APP of 2.3. Since APP is measured by periods and not by time intervals, there is no projection. It is perhaps easy to assume that if all of Bey’s matches required six full minutes, his APP would have been even higher. He didn’t have enough time to generate more attempts. Another way to look at is that Bey didn’t need to go crazy with attempts because he was consistently achieving multi-point scores.

Bey’s ACR rang in at 2.1, a little lower than Joe Rau‘s (87 kg, TMWC/IRTC) 2.3 from the Pan Am Championships. The assigned value of this statistic was not enunciated properly in the introductory article featuring Rau. A low ACR combined with a high points yield demonstrates remarkable efficiency. An athlete who exits a match or full tournament with an ACR hovering between 2.0-2.4 received scores either at or near every other attempt.

Again, one statistic by itself is not sufficient because that leads to a imbalanced numerical burden. The objective is to follow the breadcrumbs by comparing individual statistical categories and then deciphering whether or not there is a correlation between numbers. In Bey’s case, there sure is.

His APP of 2.3 is only one side of the coin. The other is an enormous PPM. Combine these stats with a 2.1 ACR, and what you have is a level of production that reaches rarefied air. And if there is high-quality footage of how this all transpired to go along with the numbers, you’ve also got yourself a very powerful marketing tool if leveraged appropriately. That is, without question, ultimately what this entire endeavor is all about: generating a complete picture of which an athlete is capable of in hopes of driving fan interest.

Bey’s high water mark for total attempts in a match came against Makhmudov in the final. He had six total attempts going for gold and converted on two of them (ACR = 3.0). But wait: he scored 15 points and only converted two attempts? Something doesn’t jive, especially since Bey did not receive credit for any par terre points in the final.

What gives?

Counter scores.

Counter Scores — Not Attacks

Prior to publish last week, Dennis Hall insisted on including a mechanism to recognize “Counter Attacks” because he, perhaps correctly, feels that reactive scores require their due respect. He is not alone, either. Others have chimed in to declare their enthusiasm for the concept of defining and calculating counter attacks if only because leaving this statistic out would be willfully ignoring an at-times abundant source of points. Fair enough.

But the term “counter attacks” also would appear just a bit opaque. Attempts is a suitable synonym for attacks; just as well, a worthy argument could be made that many counters are reflexive, and not the result of a decisive action or intent. There are scrambles in Greco, too, you know. While it is true that athletes do practice situational techniques and “chains”, we don’t want to leave any actions open to interpretation when observing scoring sequences. Rather, we simply want to note the scores and account for their origin.

If an attack is made, and there is a counter in response, then both could easily be lumped in with attempts, despite the fact that doing so fails to establish a distinguishable means for categorization purposes. Thus, “Counter Scores” is the most balanced representation of a score that required reaction or reflex in order to achieve.

Putting it plainly: not all attacks, counter or otherwise, lead to scores. We know that counter scores exist because points are awarded.

Visual Examples

Makhmudov was a wonderful dance partner for Bey the first time they met. He was just as eager to hunt for points and did not shy away from Bey’s onslaught. If anything, he had to fight for scores, because if he didn’t, he likely would have been continuously accosted en-route to a tech. That is a hypothetical of course, something to avoid at all costs. The point is that action, regardless from whom it originates, translates into a pleasant tendency to create scores — for either wrestler.

Against Makhmudov, the flood gates opened. Their shared energy compelled a need for counters, and Bey obliged by picking up three counter scores in the first period (one point, two points, and four points) and another pair in the second period (both for two points) for a total of five. All five are displayed below chronologically in GIFs and/or video clips.

Makhmudov advances on Bey towards the edge, and Bey responds quickly with double-overhooks and manages to net a step-out for one point. (Image: UWW)

The second example offers a situation that is all-too-common: a defensive wrestler landing on top following an offensive wrestler’s throw. By definition, a throw is an attack. Makhmudov had reversed Bey, achieved a lock, and looked to throw. When he did, Bey — in a phrase frequently written on this platform throughout hundreds of match recaps — adjusted and landed on top. This is a counter score. Not an attack, but a response, and an impressive one.

Easy to call: Makhmudov tries to throw, Bey uses both hands to post as he descends, lands on top, and is credited with two points. (Image: UWW)

The third counter score from Bey in the first period actually is an attack. Makhmudov grabs a gutwrench; after which Bey escapes; both athletes return to their feet with Makhmudov clearly intending to use his lock for more points; Bey has the last laugh by dumping him over for two (click to play).

Example #4 is a textbook reversal from par terre bottom on the heels of a gutwrench, something for which the US program has recently become well-known.

Though defining counter scores potentially lends itself to a debate over semantics, a high percentage of Greco-Roman actions, especially from bottom par terre, should not be construed as attacks. In this clip, the defensive wrestler, Bey, had just given up a two-point turn, and then reversed his opponent, Makhmudov, achieving exposure and two points instead of one. (Image: UWW)

The fifth and conclusive example takes place right before the buzzer, and it was another land-on-top situation for Bey after Makhmudov attempted a throw.

Bey’s balance and impressive degree of overall body awareness allowed him to commandeer several Makhmudov scoring actions and take custody of the points. (Image: UWW)

It would be incorrect to suggest that Bey relies on counter scores, because he didn’t in ’17 and does not currently. He won’t discriminate when hunting down points. However, counter scores are certainly one of his strengths thanks to experience, an eagerness to earn points, and what has been unrivaled athleticism.

Counter Scores: A Separate Category

Counter scores are realized in most Greco-Roman matches, bountiful in age-group competition, and at the Senior level can quickly alter both the complexion and trajectory of a contest. This is ample reasoning for their observation. But — at least on 5PM — will still be subject to categorization separate from PPM, PPP, and PTSM.

Greco-Roman should be associated with offense above all other wrestling concepts, particularly when it comes to on-the-feet actions — hence the motivation for the first five stat categories.

Counter scores are by nature defensive, and their catalyst is, unanimously and without exception, offensive action on the part of the other wrestler. The only way in which counter scores would manifest in another statistical category is by making those categories binary. Say, creating a delineation for PPP and PPM to acknowledge defense (dPPM/dPPP). To do that, it would mean designating some points as offensive and some points, defensive. Of course if that were the approach, there wouldn’t be a need to focus on counter scores, something the people seem to want.

Which is why splicing categories in order to include oPPM/oPPP and dPPM/dPPP might be pushing it. For now, isolating counter scores as their own separate scoring event adequately recognizes an athlete’s ability to adjust, improvise, and earn points at the expense of the opposition’s attack — which is a high marker for overall competence.

In addition, counter scores, as we’ve seen, are not exclusive to on-the-feet actions. In fact, they are frequently presented during par terre situations. For example:

- “Wrestler A” attempts a gutwrench or lift, with “wrestler B” hip-heisting, stepping over, or in some cases (though a bit rare these days), standing up during a reverse lift and re-reverse lifting their opponent.

- You would not call an athlete who executes any of the above “defensive”, for they were exploiting an opportunity to score. A wrestler in bottom par terre is only considered truly defensive when they are prone, shelled, and static (or close to it).

Bottom line: the most important aspect of counter scores is the word “scores”, standing up or on the tarp.

Logging Counter Scores

Counter scores are logged according to prevalence and average. Until further notice, they will also remain a statistical category separate from PPM but will be added to CSPM, MPSM, and AMV (more on that in the next section).

Bey earned counter scores in two of his five matches.

vs. Olofsson (SWE)

Period 1: Bey — 1 counter score (2 points)

vs. Makhmudov (KGZ)

Period 1: Bey — 2 counter scores (2 points, 4 points)

Period 2: Bey — 3 counter scores (1 point, 2 points, 2 points)

Total Counter Score Points (TCSP) — 13

Add up total number of counter score points from the tournament/event

Counter Score Average (CSA) — 2.6

13 counter score points divided by five matches = 2.6

One concern on the part of several coaches has been attack initiation when standing, and to whom the score belongs. This should not present a serious dilemma. In a flurry that sees “wrestler A” and “wrestler B” exchange attempts on the feet, the wrestler who is awarded points is credited with the counter score. If points are distributed to both athletes following a clear converted attempt, the subsequent score if the result of a counter is logged. Repeat — note the score. In the majority of circumstances, the action is defined and the outcome of the sequence as determined by officials will inform the statistic. The question of Whose action was it? is up to the officials to answer and for coaches to challenge. No need to follow them into the quagmire when numbers are the only matter eligible for consideration.

How to Consider All of the Points

In order to remove mud from the water, two additional statistics are here to save the day: “Overall Points Average” (OPA) and “Overall Points Per Period”. This solves the problem, and best yet, it nudges PPM/PPP out of the way for those who find themselves hopelessly in love with gross point totals. Moreover, MPSM, thanks to generous feedback, will likewise absorb counter scores.

OPA/OPP acknowledges counter scores, as well as any and all other scores with which an athlete is credited — including passivity and caution points. In that light, it is similar to CSPM, except CSPM also accounts for points scored by opponents.

Here’s what it looks like.

Bey’s PPM at the Junior Worlds was 11.2 prior to differentiating counter scores. Without counter scores, his PPM dips all the way down to 8.6 (still terrific). But his OPA — which consists of all points awarded — rings in at 12.2, a full point higher.

Overall Points Average (OPA) — 12.2

61 total points divided by 5 matches = 12.2

Overall Points Per Period (OPP) — 6.7

61 points divided by 9 periods = 6.7

Wrapping It Up Neatly

There are two things statistics do:

- Display a numerical rendering of exactly what happened while also illustrating tendencies and patterns.

- Avail enough evidence to infer what might have happened, particularly in situations where a fan/user may have been unable to watch the contest.

One glance at Bey’s metrics from the ‘17 Junior Worlds accomplishes both. Here is his complete adjusted stat line featuring the new categories introduced in this article.

OPA: 12.2

OPP: 6.7

PPM: 8.6

PPP: 3.7

VFR: 60%

CSPM: 16.8

AMV: 6.6

APM: 4.2

APP: 2.3

ACR: 2.1

PTSM: 1.6

MPSM: 3.6

TCSP: 13

CSA: 2.6

We are still in the infant stages of assigning statistical values to Greco-Roman points and actions, and already amendments have been made. More are sure to follow as this has fast become a community project.

The most pressing item to consider is always offense. It is never not offense or offensive intent, and that is why “Points Per…” and “Attempts Per…” will go untouched, because if nothing else, they demonstrate unmistakable intent to score. They are, in a word, decisive.

But after enough back-and-forths with several coaches and athletes, as well as Gardner Wheeler from 3D Wrestler Stats, defining counter scores adds another important piece to the vast puzzle that is performance evaluation. That neither TCSP/CSA are observed in PPM/PPP (which could change) speaks more to the value of counter scores as a behavioral metric and implication of athlete tendency. As such, lumping these points in with all the rest diminishes their uniqueness.

Look forward to two more volumes in this series. Forthcoming will be a pair of par terre statistics that are necessary for fans, media, and coaches alike — followed by a special appeal to accountability with regards to governance.

Listen to “5PM37: The wildman Sammy Jones” on Spreaker.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE FIVE POINT MOVE PODCAST

iTunes | Stitcher | Spreaker | Google Play Music