In 2003, WW Norton & Company published Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game by Michael Lewis. The book details the 2002 season of the Oakland Athletics, who went on to win 103 games as well as their second-consecutive American League West title — despite operating with a bottom-barrel $44M salary for their 25-man roster following free agency departures Jason Giambi and Johnny Damon, among others. Eventually, Moneyball became a best-seller and was eventually adapted for the big screen with Brad Pitt taking on the lead role as A’s general manager Billy Beane.

What the A’s did in ’02 (and have to a large extent ever since) was dig ever so deeper into player attributes and tendencies, and measure those against perceived market value. They began to place a higher emphasis on unsexy statistics to which few previously paid much attention — but were, in their estimation, indicative of a player’s ability to maximize his opportunities during a given game. Moments in time add up. And as these moments compile in the background, they shine a light on consistency, odds of success, and above all, market worth.

For those familiar with either the text or the film, the real genius behind the A’s’, in a sense, was not Beane, not really; nor was it Yale grad Paul DePodesta, the man responsible for completely altering Beane’s perception of how players should be valued. Instead, it is all traced back to Bill James, the grandfather of Sabermetrics for modern baseball. Beginning in the 70’s with his annual Bill James Baseball Abstract, James re-imagined baseball as a series of individual data-sets, with each player (fielders, pitchers, and batters) confined to his own in-game burdens.

To James, it could all be accounted for numerically. Traditional sliced-bread statistics like batting average, RBI, and ERA were/are, in his mind, not only mere surface-level renderings of player competence, if anything, they failed to accurately demonstrate a player’s true contribution to team wins. Oddities such as “win shares”, “secondary average”, and “similar score” were elevated in importance above BA and RBI, since neither stat can be depended upon to, over the course of a season, greatly influence a team’s chances of winning.

It didn’t take years for James’ methodology to catch on, it took decades. Only one mainstream baseball book, 1984’s Dollar Sign on the Muscle: The World of Baseball Scouting by Kevin Kerrane, dare flirted with next-generation statistical models and still very much relied on old-school scout benchmarks like “makeup”.

Fast-forward to today, and front offices for every single Major League Baseball franchise employ staffs devoted to the same advanced metrics James once pored over in his basement to the delight of a small but loyal audience. Fans, fantasy baseball aficionados, and broadcasters have also latched onto Sabermetrics, if only because more numbers help paint a fuller picture of the game they love.

Wrestling, in particular Greco-Roman wrestling, does not observe secondary numbers. At all. For international competition, success is measured by tournament placings, with the World Championships and Olympics most often beginning and ending such conversation. Drill it down to American domestic concerns, and US Open titles and World Team Trials finishes comprise the bottom-line ledgers on which most are focused. In certain instances, medals earned at various other events, at home or abroad, may be trumpeted in an effort to deliver a touch more context associated with an athlete’s resume.

Credentials are useful for marketing material, biographical footnotes, and an athlete’s bragging rights. But if there are not World/Olympic medals listed, casual fans hardly notice.

Who could blame them?

Fans of every major sport (with the exception of MMA and/or boxing) have numbers to follow. In real time. On their devices, and on their TV screens. Numbers which provide in-depth insights, patterns of behavior, odds of success, and illustrate previously unseen competences. And as outlined, fans are not the primary beneficiaries of advanced metrics. Administrators and coaches abide by statistics to determine rosters, playing time, and… salary. The salary component, certainly for the time being, does not translate with regards to wrestling.

Sophisticated statistics as a mechanism to decide pay scales is neither necessary or appropriate for international competitors, Greco or otherwise. Wrestling simply does not need advanced metrics for that reason.

Rather, wrestling needs sharp, compartmentalized statistics to keep a fanbase that tends to drift constantly engaged, and for the media at large so they can gain a firmer grasp of an athlete’s in-season viability.

Everything in wrestling is macro. Which is fine. We’ve done well with rudimentary aggregates of information and compressing them for consumption. They take up less space, are easier on the eyes, and easier to say out loud.

But if Greco-Roman, or international wrestling, period, is to finally take a leap forward into the 21st century — where fans, users, and journalists have a greater understanding of and tolerance for deeper analytical dives than ever before — it is time to get micro. And to do so means incorporating customized accompanying datasets with on-the-mat performance.

Start Simple

The first step is to identify the most critical factors commonly congruent to individual success, assign meaningful values, and categorize appropriately. This is easier said than done, especially for Greco-Roman, a style in which officials enjoy a substantial degree of control over outcomes due to guideline interpretations relative to passivity and other manners of in-match governance.

There is a workaround, however. Bypass the perceived influence of the officials the same way baseball and football statistics do with umpires and referees. (Though a way does exist to account for refs in wrestling, too). In the meantime, keep the focus on the wrestlers themselves and drill-down the in-match measures of which they have a semblance of control.

Thus a question requires asking: What is the most important component to wins in Greco-Roman?

Easy — points.

But not all points are the result of what an athlete does, correct? Particularly at Senior, those pesky officials and their passives have a huge say in point distribution.

Second workaround — stick to offensive points. And for this purpose, points scored on the feet.

How are offensive points scored?

Offensive points are the result of attempts. Even if “wrestler A” makes an attempt that “wrestler B” counters and converts into his own score, the attempt on the part of “wrestler A’ was originally responsible for the point(s) haul. This occurrence is common enough to where the absence of its documentation on a wide scale leads to a misrepresentation of the facts. Points are often scarce in World-level competition. But very few bother to mind the number of meaningful attempts (actions of clear offensive intent) that may have transpired during a match — and when officials are doing their jobs correctly, they are observing said attempts and using them as a basis to help determine passivity.

In other words, the failure to acknowledge attempts made by wrestlers during Greco-Roman matches means proper credit is not being given, and that the aggression of an individual athlete is not dutifully displayed.

The First 4 Stats

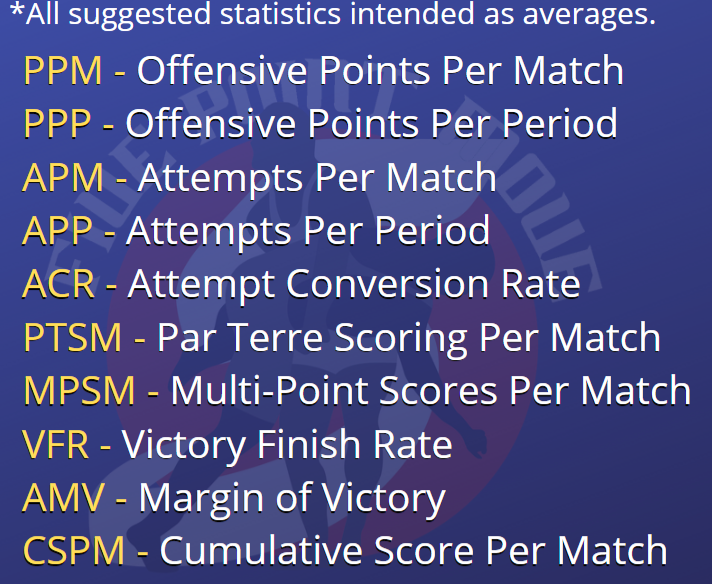

Therefore, the first two suggested statistical categories that may aid in providing a more concise glimpse at a wrestler’s behavior and approach are “Offensive Points Per Match” (PPM) and “Offensive Points Per Period” (PPP). Set as averages, both PPM and PPP at the very least indicate how active and successful (or not) an athlete is when it comes to the most important variable that decides wins.

It should be noted that PPP is constructed by observing (offensive) points scored in individual periods and determining the average. It can also be isolated per tournament for a quick perspective, or applied to entire seasons.

The same spirit is applied to attempts with “Attempts Per Match (APM) and “Attempts Per Period” (APP). Moreso than points, attempts are a vital indicator of a Greco wrestler’s willingness to score.

As an example of how these four secondary statistical examples might reflect athlete competence, we will highlight Joe Rau‘s (87 kg, TMWC/IRTC, world #7) performance at the 2020 Pan-American Championships. Rau won the tournament with a 3-0 record and two tech falls.

In his second match, Rau received two caution points due to an infraction on Lesyan Cousin Otomuro (JAM). In the final against Carlos Munoz Jaramillo (COL), Rau benefited from two passivity points. These points were not the result of offensive actions, so they are dismissed when tallying Rau’s PPM and PPP.

Rau def. Luis Avendano Rojas (VEN) 8-0, TF = 8 offensive points

Rau def. Lesyan Cousin Otomuro (JAM) 11-2 (2 caution points) = 9 offensive points

Rau def. Carlos Munoz Jaramillo (COL) 6-0 (2 passivity points) = 4 offensive points

PPM — 7

21 offensive points divided by 3 matches = 7

PPP — 4.2

21 offensive points divided by 5 periods = 4.2

Coming up with PPM is easy. Add up all of Rau’s points from his three matches, deduct the passivity points, and find the average. Rau’s PPM in Ottawa was exceptional, and his PPP sparkled because he scored nine offensive points against Cousin Ottomuro in the first period.

But– how did Rau score so many points? If you watched his matches (or read their descriptions), you know that he basically bullied everyone around, grabbed a few takedowns, cranked out some gutwrenches. He was motivated, inspired, and the Pan-Ams served as a wonderful warm-up for his more important run the next weekend.

Except none of that has anything to do with efficiency. This is where documenting attempts makes a big difference.

Defining what is and is not an attempt never ceases as a hot topic. Greco matches are full of short drags from the pummel, snaps, fleeting opportunities to lock hands around the body, and push-pull setups that too often don’t go anywhere. One could form a reasonable argument that all of the above indeed are attempts; but unless the initiating combatant causes or compels a discernible defensive reaction or aggressive counter, these three examples should be readily dismissed as the natural byproduct of two wrestlers who are intently engaged.

If a wrestler hardly has to adjust their position to ward off an advance, they were never in imminent danger of surrendering a score, nor were they forced to improvise. There might be some flexibility with regards to defining attempts, but the whole idea of defining something in the first place is to remove subjectivity — aka, the biggest problem with the Greco-Roman rule-set.

This includes loosey-goosey arm spins that wind up as slips. Calling those attempts, in most cases at Senior, would be a very generous gesture.

When it comes to attempts, Rau’s gold-medal showing at the Pan Am Championships provides further insights.

vs. Avendano (VEN)

Period 1: Avendano – 1 attempt; Rau — 2 attempts

Period 2: Avendano – 3 attempts; Rau – 2 attempts

vs. Cousin Otomuro (JAM)

Period 1: Rau — 5 attempts; Cousin Otomuro — 1 attempt

vs. Jaramillo (COL)

Period 1: Rau — 3 attempts

Period 2: no credited attempts for either wrestler

APM — 4

12 attempts divided by 3 matches = 4

APP — 2.4

12 attempts divided by 5 periods = 2.4

Rau does not get credit for an attempt in the second period against Jaramillo, whom on video does not portray the kind of zeal one might expect from a wrestler who needs to score just to stay in the match. But — we’re not worried about what influence the opposition might have had on the result.

For instance, Jaramillo was timid throughout the entirety of their bout. This likely had to do with Rau’s physical presence and superior positioning. Jaramillo, save for a flash to the body or two, really didn’t demonstrate an eagerness to score or take risk. But since the microscope is on Rau’s output and no one else’s, it is immaterial. You’re being called upon to look at Rau’s attempt stats after the fact, not Jaramillo’s. Rau’s attempts in the first period did not directly lead to scores, but he did receive a passivity point and turned Jaramillo for two.

Setting a precedent for what constitutes an attempt in conjunction with comprehending an athlete’s approach is in addition obviously crucial. What do Rau’s attempts on the feet normally entail? A quick answer would be bull-rushes to the body off of two-on-ones and drags. They are hard to miss, because even when unsuccessful, the opposing athlete is forced to react as Rau goes on the pursuit.

Rau’s match versus Avendano ends with an outlier example due to its craziness but zeroes in on just how influential attempts in a match often are.

In the second period, which did not last too long, Avendano is credited with three attempts: he doesn’t actually come close to scoring anything other than a step-out, and this is all a sloppy mess for both athletes. But on Avendano’s third and final attempt — following a wild cat-and-mouse sequence that went from one side of the mat to the other — Rau countered, covered, and gutted to victory. Avendano still gets a nod for the attempt, even if it didn’t turn out how he would have preferred. Because — attempts have a habit of creating action, even if the wrestler who initiated the action is unable to execute.

This brings up the fifth stat that shall be introduced: “Attempt Conversion Rate” (ACR).

ACR

Just as telling as attempts themselves is ACR, the true marker of competitive Greco-Roman efficiency. The number of times an athlete tried to score compared to the number of times they did score is useful for coaches and fans alike, along with — perhaps — offering the clearest picture of how aggressive and proficient an athlete has been against their competition.

Rau’s ACR on March 6 was solid but not off the charts. This is to be expected. Scoring is not easy. Rau was heads-and-shoulders above his competition in Ottawa, but it wasn’t as if each and every time he demonstrably tried to attack that a score soon followed. The higher the caliber of competition, the lower an ACR is likely to be in matches that necessitate all six minutes to decide.

vs. Avendano (VEN)

Period 1: Avendano – 1 attempt, 0 scores; Rau — 2 attempts, 0 scores

Period 2: Avendano – 3 attempts, 0 scores; Rau – 2 attempts, 1 score (four-point sequence)

vs. Cousin Otomuro (JAM)

Period 1: Rau — 5 attempts, 4 scores (1 step-out, 1 feet-to-back, 2 takedowns)

Cousin Otomuro — 1 attempt, 1 score

vs. Jaramillo (COL)

Period 1: Rau — 3 attempts, 0 scores; Jaramillo — 0 attempts, 0 scores

Period 2: no credited attempts for either wrestler

ACR — 2.40

12 attempts divided by 5 scores = 2.4

This is the stat that may show the most promise because it demonstrates how active and effective an athlete was on the feet with zero prejudice. For coaches, it answers the “attempts question” (‘Well, did he even try to score?’) as well as provides a seamless benchmark from which to measure progress (e.g., ‘He made four attempts in the match and scored on two of them; last match, he made three and didn’t score at all.’) It can also be weighed against an athlete’s personal goals. Dennis Hall, who was consulted for this endeavor, aimed to make a meaningful attempt every :30 of a match. It didn’t always happen, he was not in control of his opponents’ approaches or how the officials governed. But keeping this goal in mind helped him set a reasonable objective that doesn’t take much effort to quantify later, certainly not on an individual basis.

As for fans who actually tuned in to watch an event, they can go back and reference ACR and compare it to past tournaments as a mechanism to track the strides made by some of their favorite wrestlers. Depending on how nerdy devoted they are.

The one hangup? ACR is subject to five separate point values: step-outs (1 point); takedowns (2 points); correct throws (2 points); four-point throws; and naturally, five-point throws. It does not discriminate based on what the end result of a successful attempt happens to be. Then again, that is why you have other statistical categories available. It is reasonable to conclude that if an athlete boasts an ACR of 2.4 and a PPP of 4.2 following a tournament, he must have executed at least a few multi-point scores.

ACR is simply a conceptual baseline and can be tuned for specifics rather easily. Those interested in conducting a more intensive drill-down have the ability to break down the numbers much further. Figuring out an athlete’s ACR when they score on four and five-point holds would present a whole new dynamic when examining offensive might.

Admittedly, all of the Greco stats being suggested here require much more in the way of exploration so as to adequately determine fitful bedrocks for comparison. But the feeling is that even with the benefit of a wider study, the majority of “top-tier” events will feature competitors with mid to low ACR numbers, particularly in heavier weight classes. Attempts on the feet are, unfortunately, often not plentiful, which is why there is such a premium on scoring. If ACR accomplishes anything, it provides an evidence-based rendering of the kind of skill to which most elite competitors are beholden.

Now for Par Terre

Par terre scoring (so long as it remains in the rule-set) is fun to watch, easy to account for, and wholly evocative of top-level Senior Greco-Roman competence. The very best tend to leverage par terre for the brunt of their scoring. Similarly, a wrestler’s defensive ability from par terre bottom is also important and worthy of recognizing, and would present a valuable statistical reference. But for now, we’re going to continue to stick with offense since that should be what people think of first pertaining to Greco competition.

Par terre scoring for this purpose (“Par Terre Scoring Per Match”, or PTSM) is observed from static, and definitively not the result of a continuous action on the feet. Ordered par terre, a reset in par terre, or following a takedown once the defensive wrestler is prone and the top wrestler is yet to have a lock or hold, are the starting points.

As an example, one of Jesse Thielke‘s (60 kg, Army/WCAP) biggest strengths is using a duck-under that allows him to lock the body and immediately score a takedown and follow-up gutwrench. That type of action begins on the feet, and is not from a par terre position that promotes an equal opportunity for both the top and bottom competitors to act or react. There is already a lock, already motion. Avid viewers of the sport are well aware of how this unfolds. An explanation would only seem necessary because the back-end of the sequence is a gutwrench, thus potentially confusing newbies.

Thielke hit an even nicer duck to bodylock against Donior Islamov (MDA) to close out this match, which took place in the semifinal round of the 2016 2nd OG World Qualifier in Istanbul. Looking closer at this sequence, it is obvious that Thielke’s momentum and direction, plus his lock, are going to lead to a gutwrench upon landing. But since the lock is secured on the feet, and since it is on the feet where the action and momentum were created and there was no reset, the two gutwrench points would not be counted as having originated from par terre. It seems simple, but a delineation must be made in order to curb misinterpretations before they begin. (Image: UWW)

We bring it back to Rau, who is a very strong par terre wrestler and scored 10 points from top in the ’20 Pan-Am Championships. Although, not all of them would be eligible for consideration as par terre points.

In the first period against Avendano, Rau counters an arm throw and yanks back for two points. That is not a par terre score, it is a counter attack (more on that in the summary). But — Rau did soon gain another score while Avendano was beneath him, and those two points were derived from par terre.

The match-ending sequence sees Rau hustle for a takedown after the brawling exchange presented in the clip above. As soon as Rau attains the offensive position on top, he runs a gut. This is a textbook par terre score deposited right in the bank.

Par terre scoring is capable of being categorized in terms of both average points and success percentage. Fans might find it more practical to glance at the former, while coaches can use the latter to detect improvement.

Rau’s PTSM in Ottawa on March 6 is deceptively low for a wrestler who won two matches via technical superiority and shut out his opponent in the finals (thanks in large part to a pair of gutwrenches).

vs. Avendano (VEN)

Period 1: Avendano – 0 par terre offensive points; Rau — 2 par terre offensive points

Period 2: Avendano – 0 par terre offensive points; Rau – 2 par terre offensive points

vs. Cousin Otomuro (JAM)

Period 1: Rau — 0 par terre offensive points; Cousin Otomuro — 0 par terre offensive points

vs. Jaramillo (COL)

Period 1: Rau — 2 par terre offensive points; Jaramillo — 0 par terre offensive points

Period 2: Rau — 2 par terre offensive points; Jaramillo — 0 par terre offensive points

PTSM — 2.6

8 par terre points divided by 3 matches = 2.6

As is the case with ACR, PTSM is ripe for customization. It can be sub-categorized according to point values, which would perhaps shine a brighter light on an athlete’s methodology.

Other Statistical Categories Worth Exploring

Multi-Point Scores Per Match (MPSM) — Techniques/attacks resulting in more than one point (takedowns, throws, gutwrenches, lifts, etc.). Referred to in the section for ACR, MPSM isolates offensive sequences both standing and from par terre.

Rau vs. Avendano

Rau — arm throw counter to exposure, high-gut lift, takedown, gutwrench = 4 multi-point scores

Rau vs. Cousin Otomuro

Rau — takedown, feet-to-back, takedown = 3 multi-point scores

Rau vs. Jaramillo

Rau — gutwrench, gutwrench = 2 multi-point scores

MPSM — 3

9 total multi-point scores divided by 3 matches = 3

Victory Finish Rate (VFR) — How often an athlete wins via technical fall or fall. Bouts which end prematurely due to cautions, disqualification, etc., are not observed in this statistic.

Rau def. Avendano 8-0, TF

Rau def. Cousin Otomuro 11-2, TF

Rau def. Jaramillo 6-0

VFR — 66%

2 tech falls divided by 3 matches = 0.66

Margin of Victory (AMV) — The average point differential in wins for an athlete.

Rau def. Avendano 8-0, TF = 8 points

Rau def. Cousin Otomuro 11-2, TF = 9 points

Rau def. Jaramillo 6-0 = 6 points

AMV — 7.6

23 total points divided by 3 matches = 7.6

Cumulative Score Per Match (CSPM) — Could be titled “Average Combined Score”, but isn’t because of assumed implications towards offense. CSPM is the only statistical category proposed that accepts points acquired by means other than offensive techniques/attacks, or defensive counters. You are looking at all of the points with this one. In other words, passivity points and caution points are included. To calculate CSPM, simply add up the scores of both wrestlers from individual matches and divide by the appropriate denominator.

Rau def. Avendano Rojas (VEN) 8-0

Rau def. Cousin Otomuro (JAM) 11-2

Rau def. Munoz Jaramillo (COL) 6-0

CSPM — 8.3

25 total points divided by 3 matches = 8.3

Applying the methods introduced above, Rau’s stat line from the 2020 Pan-Am Championships reads like this:

Place — 1st

Wins — 3

PPM — 4

PPP — 4.2

APM — 4

APP — 2.4

ACR — 2.40

PTSM — 2.6

MPSM — 3

VFR — 66%

AMV — 7.6

CSPM — 8.3

Summary

The potential for actual, presumably-relevant statistics (aside from wins, losses, and hardware) for wrestling does not exist in a vacuum. Several collegiate teams go the extra mile and measure different aspects of competition and use what they find to make tweaks in their training plans. Moreover, Gary Mayabb, USA Greco-Roman Manager of Programs, has his own datasets that the National staff employs when it comes to evaluating athletes. Digging under the rubble of matches and tournaments in an effort to ascertain causes and effects, successes and failures, and signs of improved performance has become normal. Coaches everywhere now have access to a variety of software they can use to upload video, clip scoring sequences, make notes, and track all kinds of data, if they so choose.

On a grander scale, It comes down to trying to determine what an audience wants to consume. Greco fans are ready for stats. For sure. But that is mostly because folks who are into Greco (usually) understand there is a whole lot more that goes on during a match between two high-level athletes that never shows up in a typical box score. You get points, technical and classification, and that’s it. No one in the US cares about classification points, anyway, and final scores on their own are useless because they are bereft of even the slightest sliver of context.

The thought is, and has been, that Greco-Roman has a presentational problem. There are wrestling fans who want to get into Greco, but can’t or won’t because they are either confused over the rules, not in love with grinding pummel-fests, or are unfamiliar with basic positions and strategies. On the flipside, fans who are devoted to watching Greco — or any style of wrestling — like the idea of compartmentalized stats. They are ready to follow along closely, to compare and contrast, and then talk about what it all means leading up to major events.

But Greco is not presented in a manner befitting of a major sport given the digital landscape. Again, wrestling as a whole isn’t, but other styles are not the concern on this platform. If fans are unable to watch events live or via internet stream, they look up results. When they come to 5PM, sure, they’re going to be welcomed by match descriptions in a blow-by-blow format that hopefully captures the essence of the action. That’s nice. Except with increasing frequency, fans are thirsting for more. More analysis that is as free of biases as possible to complement what they watch on-screen or read in article recaps. Our solution will be to try and offer more statistically-heavy material going forward, but it is highly-recommended that the entirety of wrestling, from sanctioning bodies to media outlets, consider traveling a similar route for their own styles provided the manpower is available.

And that’s the thing. A great deal of time-consuming legwork is involved with unearthing statistics. A lot of watching and re-watching matches, referencing scores, checking and re-checking. For the purpose of this article, Rau’s performance was used because it was easy: three matches that were lopsided and without controversy. To drum up the same stats for every US athlete at the Pan Ams would have likely required multiple days, and that is only one tournament. I’ve dipped my toe into metrics before, and as mentioned, will be doing so more often; but to really dive into the numbers on a consistent basis is not in the immediate plans around here at the moment. My goal for this article is to merely showcase a different supplemental avenue that might facilitate a richer appreciation for Greco and overall fan experience, as well as serve up a few ideas for how coaches can evaluate talent.

Most of the suggested statistical categories in this piece were conceived over the course of several years after participating in countless discussions with athletes, coaches, fans, and other media members. Hall’s input made an impact, and surprisingly, he approved of all the verbiage used to explain each statistic. He was particularly fond of the metrics proposed for attempts but also felt, passionately so, that a statistic be applied for “Counter Attacks”. Hall cited a essay from legendary Russian heavyweight Alexander Karelin, who intimates in his own piece how and why counter attacks affect outcomes with a substantial degree of prominence. Soon, Hall and I will collaborate on a way to construct, observe, and calculate counter attacks and test what we find against a series of matches. “Wins By Criteria” is another possibility, though that one will have to wait. We’ll talk about it.

For now, that is precisely the driving force to this editorial. To experiment a little, to at least plant the seeds and start a conversation. Whether you embrace the idea of stats, are on-board with what has been presented in this article, or scoff at the crudeness of it all, what you think and have to say matters. For Greco to wedge itself more into the wrestling mainstream, more has to be offered. More voices need to be heard, more desires, met. If some of that can come from a collection of fabricated metrics instead of technique highlights and wordy paragraphs bordering on pedanticism, so be it.

Listen to “5PM37: The wildman Sammy Jones” on Spreaker.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE FIVE POINT MOVE PODCAST

iTunes | Stitcher | Spreaker | Google Play Music