With a few days of distance, it has become easier to compartmentalize Team USA’s collective performance at the 2016 Rio Olympics. There were only six total matches involving American wrestlers, so recalling the basics of what took place at the Carioca 2 Arena takes but a couple of seconds. Jesse Thielke (59 kg) rolled over Mehdi Messaoudi (MAR) and then had the tables turned on him by 2011 World Champion and two-time Olympic silver medalist Rovshan Bayramov (AZE). Andy Bisek (75 kg) defeated familiar foe Yurisandy Hernandez (CUB) in a tight first round bout before dropping an equally-tight decision to Bozo Starcevic (CRO). Ben Provisor (85 kg) pretty much waffle-ironed 2015 World silver Rustam Assakalov (UZB) but didn’t score enough points to reflect his actual output. And heavyweight star Robby Smith carried a two-point lead into the second period before he, too, saw his gold medal hopes evaporate after being put down in par terre.

No gold medals. No medals, period. It’s what happened. There is no hiding from that. At the same time, there is a sense of frustration that is growing too intense to ignore. These Olympiad was strongly implied to be taking place during a pivotal time in the US Greco program’s history. Naturally, in a results-oriented sport, the actual action which unfolded is largely dismissed. People see 2-4. They saw no medal rounds. There wasn’t even a repechage match to be found. But if you take a somewhat closer look and peer into the fabric of the team’s performance as a whole, you should notice that there was more going that at the very least, deserves further scrutinizing.

1. Bright spots on a couple of cloudy days

As a whole, this wasn’t a whitewash. It was not like four American Greco Roman wrestlers went into the big, bad Olympics and got steamrolled right out of the tournament. Thielke had a first-round opponent who he was supposed to beat and did, emphatically. The Wisconsinite didn’t hit any of his nasty ducks or laser-sighted bodylocks on the feet, but he didn’t need to. He got the first shot at par terre and away he went. Of course, he wound up dying by that same sword against Bayramov. So have plenty of other wrestlers with far more distinguished pedigrees. You don’t take solace from this. Nor do you give Thielke a pass. After all, he doesn’t give himself one. But the kid won a match in the Olympics for crying out loud. Was he tabbed as a gold medal favorite by the press at large going into Rio? Maybe not. Was he a viable medal contender, especially coming off of his run in Turkey? Yes. So that’s frustration angle #1.

Provisor looked as good, if not better than the machine he was in Iowa City at the Olympic Trials. The 26-year old drew a tough assignment right out of the gate and proceeded to pound him into near submission. Provisor knocked Assakalov down two or three times; he completely owned him physically. But because of that fact, he also left a decent number of points off the board he could have capitalized on. When Provisor got loose off of his gutwrench attempt and was subsequently reversed, that could have been a portent of things to come. Only it wasn’t. He recovered, got a point back and then, as is nearly custom by now for Americans, was penalized and he couldn’t defend. Provisor kept pushing and pushing, he clearly had Assakalov in deep water, even coming away with two caution points. Too little, too late. We’ll tab that as frustration angle #2.

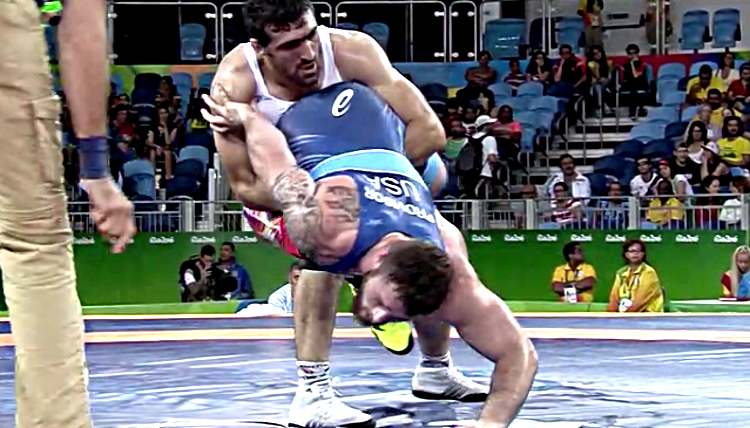

Robby Smith collected two off an arm-throw attempt right away against eventual bronze medalist Sabah Shariati (AZE). It was especially encouraging considering the last time these two battled at the Golden Grand Prix, Shariati did his best to ball Smith up and suffocate his offense. Smith was prepared and pounced on the first opportunity that came his way. But just like Thielke, Smith was unable to ward off his opponent’s par terre attack, resulting in a crushing 8-2 defeat. We’ll leave Smith getting knocked twice by the official in a matter of seconds out of it for now.

2. Screw jobs

Rocket science – (noun) – The science of designing or building rockets. (Miriam Webster)

Passivity – If a wrestler is blocking, keeping his head down on his opponent’s chest, interlocking fingers, or in general avoiding open wrestling in standing position (refusing to come back on a straighter upper body position).

In case (sic), if the bout reaches 4:30 and the score is still 0:0, the referee will stop the bout and the refereeing body will choose a wrestler as passive and they will give 1 point to his/her opponent and ask him for the position (either standing or par terre position). (United World Wrestling International Wrestling Rules, March 2016)

To sum this up, it takes less words to define “rocket science” in its native context than it does “passivity” by the global governing body. That…is a problem. It is also one that showed itself over and over and over again at the Rio Olympics and certainly was on display whenever the US Greco Roman wrestlers were competing.

Forced par terre, which we will go into in more detail at a later time (the only reason why we had not done so sooner is because we felt it was comprehended correctly by the masses. We were right. It’s the officials who have muddled it up) was designed in part to encourage looser wrestling and by extension, discourage a “play it safe” approach. Most are on board with that line of thinking. Sure, the whole “choosing a wrestler as passive” end of the equation is at best fascist and at worst potentially corrupt, but let’s ignore that for a second. Everyone knows the rules by heart. Certainly the competitors did heading in. Therefore, it’s not a viable excuse. US wrestlers, particular US Greco Roman wrestlers, should already be aware going in that if anyone is going to be screwed, it’s going to be them. Thus, are they starting international matches already down two strikes? You might know the answer. It isn’t even funny to pretend this is some grand conspiracy because the thing is, no one is laughing.

Thielke was going to get put down if he didn’t stick his sternum into Bayramov and run him off for a four-pointer. That’s fine. He undoubtedly was keen of that entering the match. So when he was knocked early on in the first it was hardly a surprise. Now, he didn’t defend and got gut-tech’ed. USA challenged, it didn’t work out. But it is what it is. That end of things is on Thielke. He’ll tell you that. But Bisek? Bisek was forced to assume the position in the second period against Starcevic, was close to fighting it off and ultimately couldn’t. Was Bisek “keeping his head down on his opponent’s chest” or “avoiding open wrestling?” Ask yourself this — Have you ever even seen Bisek compete that way? Of course you haven’t. But the rules are the rules, right? No — it was a hosing. Bisek was probably somewhat surprised by the high lock by Starcevic, who knows? But he probably wasn’t surprised by having to hit the deck in a tight match on international soil. Frustration angle #3.

You could say the same thing about Smith. Kind of. Smith does have a habit of letting his head rest against an opponent’s chest, although that is because he is often comfortably shorter than his 130 kg opposition. But jeeze, have you seen another heavyweight who tries to flick off finger-locking attempts more than him? Have you seen another heavyweight try to pummel inside as relentlessly? Gosh, no one is saying Smith was supposed to storm through this thing by any stretch. But if there is one thing the guy does, it’s constantly work. Not that it matters. Smith was passive knocked twice within a hilariously short amount of time in the second period. He had to go down. He did. To the tune of an 8-2 score.

Provisor’s case is similarly egregious. You could make a reasonable argument that Provisor wrestled just as well as anyone else in the group, including Thielke and Bisek, who both picked up first-round wins. Aggression doesn’t win matches. Taking advantage of positions does. It’s an uncomfortable concept, but one that is true. That being said, Assakalov had such a low gutwrench locked onto Provisor, it was practically a leg-lace. Look, there are always going to be low-locking gutwrenches which fall a little too low, but officials can’t call all of them, nor would we want them to. But the lock Assakalov had was just soooo low you have to wonder how the referee missed it.

Assakalov’s grasp fell below the hips, but was not called back by the official.

Assakalov’s hold slid down. That isn’t unusual, specifically at the higher weight classes. But in this case, it slid way down. It was also executed for four points. Provisor shouldn’t have been penalized and put down in the first place, but once again, rules are rules. Provisor was called upon to pay the piper and he did.

Do any of these examples mean wins were stolen away? It would be a leap to presume such. Nevertheless, they deserve to be highlighted simply to show that whether it’s a Zagreb, a Golden Grand Prix, or the Olympics, the United States athletes are operating with a barely-visible margin for error. If you didn’t notice at least that Sunday and Monday, seriously, you don’t really know what you were watching.

3. The draws actually weren’t terrible

Every match at the Olympics, Greco or otherwise, is supposed to be against world-class competition. Not one guy is intended to be an easy out, even with this year’s placement of the World golds and silvers on opposite ends of the bracket. If you’d like to put your “fan hat” on, Bisek was the betting favorite to get past Hernandez. Hardcore vet and 2015 80 kg World champ Selcuk Cebi (TUR) would have been a challenging bout for the Minnesota native, but one that was certainly doable. Starcevic, who had the tournament of his life on Sunday, took care of that problem. So you drummed it up like this before the quarterfinal: Bisek gets by Starcevic and then it’s Vlasov. Vlasov would have been no picnic, but Bisek has beaten him before and there is just something stylistically about that match-up to like.

It’s a tall order to take out someone like Baryramov, but the match-up that would have led to for Thielke promised to be tremendous. Shinobu Ota (JPN) definitely would have been seen as a fun semifinal scrap and one he potentially would have done very well in. Ota’s style is not all that far away from Thielke’s. They both like to score on their feet and both have some dogfight in them. Maybe that Ota had defeated Soryan twice in the same calendar year would have represented some daunting uphill battle, but be reasonable. If that match had come to fruition, most in the US would’ve been glad to take Ota over Tasmuradov or Borrero if those two were on Thielke’s side of the bracket instead.

Provisor and Smith weren’t blessed with the easiest roads to hoe. Provisor’s quarterfinal round opponent would have been two-time World bronze medalist Viktor Lorincz (HUN). Not a cakewalk. If Provisor came in with a full year’s worth of competition under his belt, you’d feel more confident about that one. Then again, he sure softened up Assakalov for Lorincz though, didn’t he? Smith, had he defeated Shariati, was going to be walking into the buzzsaw that is two-time World Champion and 2012 Olympic bronze medalist Riza Kayaalp (TUR). Kayaalp and Smith have a limited history and it’s not a good one. But that’s what this is all about. The draws should be difficult at every tournament, let alone the Olympics. We’ll say the US was given two somewhat favorable draws and two that definitely resided on the other end of the scale. Frustration angle #4.

4. This was a great team

A two-time World medalist, a previous Olympian, a heavyweight who at 29, is still on the rise, and a fiery young talent already armed with credible international experience. That is who showed up in Rio. Other countries might trot out bigger names with longer resumes, but that is almost always the case. The US functions with a much thinner roster, despite the fact there couldn’t have been another four athletes better prepared than who wound up going. There was the perfect amount of seasoning, or so it seemed. No one wanted to see Thielke standing across from them at 59 and damn straight nobody at 75 wanted to have anything to do with Bisek. Smith entered Rio as someone who had taken fifth at two separate Worlds and is just finding his stride later in his career. Ben Provisor had already learned what it was like to step foot inside an Olympic arena and if there were any doubts about him, they were washed away along with Assakalov’s respiratory system.

Regardless of what is heard from the naysayers, this was the right group. Bad breaks, defensive breakdowns, opportunities once present, then disappeared. The sequence of events which unfold during a singular match aren’t too difficult to notice, provided your eyes are open. All it takes is one miscue, one call that doesn’t make sense, one error by an athlete (or an official), and everything gets turned upside down. There were medals inside of these four. The objectives were not reached, waving from a distance, taunting us all in their elusiveness. It does not make a difference — these were the right men at the right time. All you could ask for is an Olympic team where each member believes he is there to win. That’s what you had in 2016. Hopefully, you don’t forget it.

Notice: Trying to get property 'term_id' of non-object in /home/fivepointwp/webapps/fivepointwp/wp-content/themes/flex-mag/functions.php on line 999